September 7, 2011 — The sharpest images ever taken of Apollo landing sites as seen from lunar orbit were released Tuesday (Sept 6.), offering a crisper view of the hardware and tracks left by astronauts 40 years ago.

"You can see very clearly both the astronauts' tracks and the really beautifully sharp and crisp parallel lines, which are the tracks of the lunar roving vehicle," Mark Robinson, principal investigator for the camera on NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), said of the Apollo 17 view, one of the three landing sites that were newly imaged.

Circling the moon since June 2009, LRO first imaged the Apollo landing sites at a distance of about 62 miles (100 km) above the lunar surface. Then, after lowering into its desired orbit, the spacecraft captured each of the six sites again from about 31 miles (50 km) away. Those images offered the first look at Apollo hardware and moonwalkers' tracks since the astronauts were there.

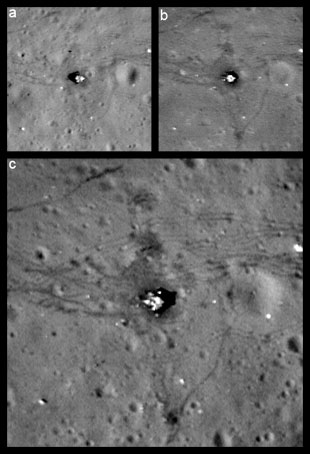

Resolution comparison between nominal orbit images of Apollo 17 landing site (a, b) and the sharper low orbit image (c). (NASA) |

For these new, sharper images, LRO dipped as low as 13 miles (21 km) above the surface for about a month. The brief time and the orientation of LRO in its orbit meant that it could only photograph three of the six landing sites: the second (Apollo 12), third (Apollo 14) and last of the lunar landings (Apollo 17).

"We only spent one month in this very low altitude orbit and because the ground track of the spacecraft crosses the moon not always over each of the Apollo landing sites — since the six landing sites were distributed across the face of the moon — it wasn not possible to image easily all six sites," Richard Vondrak, LRO project scientist said. "Some of the illumination conditions weren't optimal... the Apollo 11 site in particular."

Revealing revisit

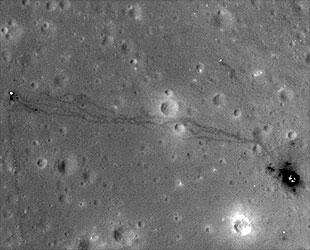

All three landing sites' images show distinct trails left in the soil when the astronauts exited the lunar modules and explored on foot. In the view of the Apollo 17 landing site, the bootprints, including the last path made on the moon by humans, are easily distinguished from the dual tracks left by the lunar rover, which remains parked east of the lander.

"Some of the tracks that were too faint to be seen before are now visible. Tracks that we've seen [in earlier images] are obviously sharper. The rover tracks are now being resolved much better than they were before. And just like the human tracks, some of the rover tracks we couldn't see that are very faint are coming into focus," Robinson said.

Paths left by astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell during Apollo 14 moon walks are visible in this LRO image. (NASA) |

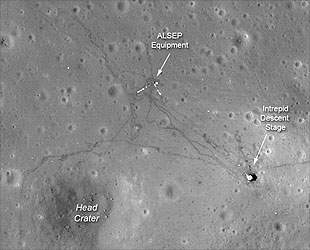

The closer views have revealed more than just rover and bootprint tracks however. They also resolved more of the experiments left behind, called the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package, or ALSEP — even more than what the project scientists expected to find.

"There seemed to be too much stuff on the ground based on looking at photographs and the layout of the ALSEP," Robinson said. "It was later that we realized that some of that is packing material and some of what we were identifying were pieces of the insulation blanket that were blown off the [lunar module] descent stage when the ascent stage blasted off. It is really pretty amazing that you can resolve all this, much better than we could in our previous images."

The new images also show the site where the American flags were planted, although the flags themselves are too small to be resolved — if they are still there at all.

"It's not really clear whether the flags are even there any more because they weren't anything special, they were made out of nylon. In the extreme heat and [ultraviolet] environment on the moon, personally I would be surprised if there's anything left on them," Robinson said.

Visceral and practical

Of course, LRO wasn't sent to the moon just to image the Apollo sites. It spent a year mapping the moon in support of future exploration efforts and is now fully devoted to collecting science data about our natural satellite.

"If you asked for a complete set of LRO data on standard DVDs, you would get a stack of 52,000 DVDs. If you took this stack and put it on the ground floor of the Capitol Building in Washington, it would reach to the top of the Capitol dome," Vondrak said.

But even the Apollo landing site data contributes to LRO's science data.

Tracks made Pete Conrad and Alan Bean can be seen in this LRO image of the Apollo 12 landing site. (NASA) |

"The tracks are neat and exciting because you get a visceral response seeing where — when we used to be able to walk on the moon — that someone walked there, but from a science standpoint, they are important for two reasons," Robinson said. "One, because they tell us something about the photometric properties of the surface of the moon. Why are the [tracks] darker? And there are scientists working with this data right now to investigate that question."

"But on a more practical sense, it allows us to find the exact spots where [moon rock] samples were collected, whereas before they were somewhat approximate. Though I'll have to admit that those people who were making the maps in the Apollo days somehow did a fantastic job placing the sample sites. But we're updating those right now," he said.

The sharper views of the Apollo hardware — the remnants of the lunar landers, experiments and rovers — are also contributing to scientific investigations.

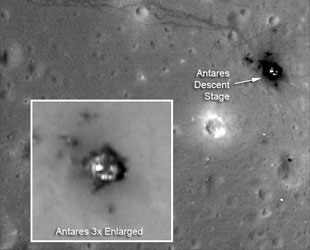

"One of the interesting facets of getting higher and higher resolution is looking at the brightness of objects. There is a big scientific controversy about the amount of the dust that moves around on the surface of the moon naturally, not involving humans. Over time, if there was a lot of dust being levitated off the surface and then deposited, things that were very bright and reflective wouldn't be any more because they would be covered in dust," Robinson said.

"So one of the things we are interested in doing, since we don't have any assets on the surface of the moon to measure this... is looking at the [thermal] blankets that are laying on the ground, the deck of the spacecraft and some of the instruments. Clearly there is not enough dust being moved around naturally to cover everything right now."

Apollo as a benchmark

The Apollo landing site images also help calibrate LRO's location, which helps all of the spacecraft's observations.

"The Apollo sites serve as benchmarks," Robinson said. "When you go hiking, you see the little [U.S. Geological Survey] benchmarks that are on mountain tops. Those are spots on the Earth that are very, very well known in their latitude, longitude and elevation. So we use these [Apollo] pictures, particularly the laser retro reflectors which are at four Apollo sites and the descent stages because their locations are very accurately known. This allows us to make checks on the accuracy of the LRO spacecraft ephemeris," or calculated position.

"We found that the error when we go over all these Apollo sites over time is roughly something like plus or minus 20 meters. If you stop and think about it, that is really, really amazing that we can take a picture on the surface of the moon and be fairly confident that any latitude and longitude that we derive from that is given to you plus or minus 20 meters. It is kind of a challenge to do that even here on the Earth."

Descent stage of the Apollo 14 lunar module Antares. (NASA) |

As such, these latest images won't be the last time LRO photographs the Apollo sites. According to Robinson, the spacecraft has been taking and will continue to capture images of at least some of the six landing locations each month. These later views however, will not be from nearly as close as those released today.

"These are the sharpest images that we will get of Apollo landing sites that we plan for this mission. Because in December we're going to go into a different orbit and we'll never at that altitude get over the Apollo sites as low as we were in this past month," Vondrak said.