August 24, 2006 — The hunt for magnetic tapes that recorded the original Apollo 11 moonwalks of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin in 1969 has swung into high gear.

A full-scale look for the original tapes is now underway at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland — the site where the material may be housed, or at another location within the NASA archiving system.

Despite the challenges of the search, the space agency maintains it does not consider the tapes to be lost.

For the past 18 months or so, NASA Goddard had been carrying out a casual look for the tapes — replaced recently by a more formal look-see.

NASA engineers are hopeful that when — and if — the moonwalk tapes are unearthed, they can use today's digital technology to provide a version of the moonwalk that is much better quality than what was broadcast throughout the world over 37 years ago.

Bolstering that belief is the fact that Goddard engineers were able to extract data from a nearly-identical type of tape recorded in 1969 of an Apollo simulation from the Honeysuckle Creek, Australia tracking station. That provides optimism that when the tapes are located, experienced tape handlers can preserve original video.

Exhaustive search

"We've kicked off an exhaustive search," said Dolly Perkins, Deputy Director-Technical at the NASA Goddard field center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "We are pulling every record we can find that has any link to the handling and storage of Apollo records."

Director of NASA Goddard, Edward Weiler, asked Perkins to be the management lead of the group conducting the hunt for the Apollo tapes.

In the event the tapes are found, steps would be taken to assure that all the unique hardware required to process the Apollo 11 moonwalk tapes is still available and can be used to make digital reproductions of the tapes. Those tapes would then be kept with the NASA History Office to make sure the video is protected and restored as needed.

Goddard's ramp up to a formal search for the tapes is good news, said Richard Nafzger, who is leading the engineering side of the search at Goddard.

"We are quite busy organizing this search in a logical manner as, prior to this, searching has been an informal — as time allows — effort on my part," Nafzger told SPACE.com.

Important clues

In responding to a SPACE.com query, Perkins said that part of the detective work is a physical search of any facility thought to have been used to store Apollo tapes, including the National Records Center, buildings at Goddard, or any storage facility that contractors may have used back then, or since.

"We are even pulling old phone books from the 1970's and 1980's so we can contact as many people as possible who worked in records management, or for the manned spaceflight program, to see if they have any information that might be valuable to our search," Perkins said. "We've received hundreds of calls and e-mails from people who think they may have important clues, and we're following up on all reasonable inputs," she added.

Perkins said that, given all the reporting on the search for the Apollo TV tapes, an important point has been lost.

"All of the important technical, biomedical and scientific information from the Apollo landings was transmitted in real time to Mission Control in Houston, recorded and preserved," Perkins noted. Those data are not lost, and are in fact secured in the nation's archives, she said.

"The one thing we don't have, because it only exists on these tapes, is the original slow-scan TV of the lunar EVAs [the moonwalks]. Only in recent years has technology advanced to the point where extracting the information digitally from the original Apollo television became a viable proposition," Perkins said.

Hopeful... but realistic

As for the search now ongoing, Perkins explained: "We're hopeful, but at the same time realistic."

Tapes of the sort being sought were highly specialized, Perkins continued, typically kept only until a mission was completed.

"It would have been common procedure to reuse such tapes for other missions or to destroy them at some point," Perkins advised.

"Our hope is that someone had the foresight to realize that this might happen one day, and put the tapes into permanent storage rather than following typical procedure," Perkins said. "Finding the records will give us the answer one way or the other."

Re-process for posterity

Stan Lebar, during his career at Westinghouse, served as Program Manager of the Apollo TV Lunar Camera which recorded the first steps onto the lunar surface by Armstrong and Aldrin back in July 1969. He and several other Apollo-era retirees stirred up early interest in finding the tapes.

"We are fighting a ticking clock," Lebar told SPACE.com, "where on the one hand the magnetic medium of the tapes have a definitive lifetime. If we wait too long we may find tapes that no longer contain recoverable data. On the other hand, those of us that were intimately involved in the Apollo 11 activity — and understand every aspect of the process that took place — are passing on in large numbers," he warned.

Lebar said that the premise of the search for the elusive Apollo 11 tapes is that the very best recording of this singular moment in the history of humankind should be made available to those that follow Apollo's small step, but giant leap.

"That very best recording is out there somewhere and the least we can do is make the effort to salvage it, re-process it and make it available for posterity before it is lost forever," Lebar said.

For details regarding the search for the Apollo 11 Slow- Scan Television Tapes, cast your eyes on these sites:

|

|

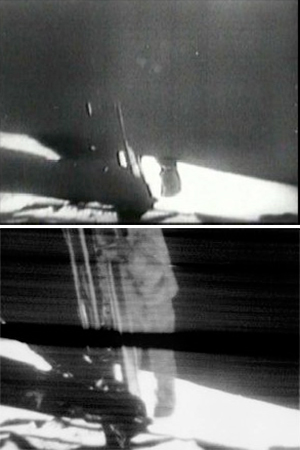

Scan-converted broadcast image of Neil Armstrong descending the lunar module ladder taken at the Goldstone tracking station. This was the image the world saw of the first human on the moon. But a Polaroid picture of the slow-scan television image reveals greater detail. (John Sarkissian/CSIRO Parkes Radio Observatory)

A Polaroid of a slow-scan image taken at the Goldstone tracking station reveals far more detail than publicly broadcast TV during Apollo 11 moonwalk. A search is underway to locate old Apollo tapes and freshen them up with digital technologies. (Bill Wood) |