August 14, 2006 — Back in July 1969, the first moonwalks by Apollo 11's Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are frozen forever moments in the history books. But it turns out that millions of riveted spectators back on Earth were on the receiving end of substantially degraded television showing the epic event.

The highest-quality television signal from Apollo 11's touchdown zone in the moon's Sea of Tranquility — from an antenna mounted atop the Eagle lunar lander — was recorded on telemetry tapes at three tracking stations on Earth: Goldstone in California and Honeysuckle Creek and Parkes in Australia.

Scads of the tapes were produced — and now a search is on to locate them. And if recovered and given a 21st century digital makeover, they could yield a far sharper view of that momentous day, compared to what was broadcast around the globe.

But Apollo 11 is a memory rewind — now over 37 years old. Nobody is quite sure just how much longer the original slow-scan tapes will last... that is, if they haven't already been erased.

Handled and archived

"I would simply like to clarify that the tapes are not lost as such, which implies they were badly handled, misplaced and are now gone forever. That is not the case," explained John Sarkissian, operations scientist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization's (CSIRO) Parkes Radio Observatory in Parkes, Australia.

Sarkissian said the tapes were appropriately handled and archived in the mid 1970's after the hectic activity of the Apollo lunar landing era was over. "We are confident that they are stored at [NASA's] Goddard Space Flight Center [in Greenbelt, Maryland]... we just don't know where precisely," he told SPACE.com. It is important to note, Sarkissian added, that there is no inference of wrong-doing, incompetence or negligence on the part of NASA or its employees.

"The archiving of the tapes was simply a lower priority during the Apollo era. It should be remembered, that at the time, NASA was totally focused on meeting its goal of putting a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No sooner had they done that, than they had to repeat it again a few months later, and then do it again, repeating it for a total of seven lunar landing missions... including Apollo 13," Sarkissian pointed out.

Making it tough to track down the whereabouts of the data, many of those involved in the archiving of the tapes have since moved on, retired or passed away, "taking their corporate memory of where the tapes are with them," Sarkissian said.

It is important not to exaggerate the quality of the images being sought, Sarkissian added. "The SSTV was not like modern high definition TV and nor was it even equal in quality to the normal broadcast TV we are accustomed to viewing," he said.

Still, the SSTV was better than the scan-converted images that were broadcast at the time — which is the only version currently available, Sarkissian concluded.

Paper trail

A small independent group of Australian and U.S. Apollo tracking station veterans have embarked on a new search for the Apollo 11 tapes.

The group is hot on a cold paper trail regarding the location of the data. They're also on the lookout for anyone involved in the management, disposition and storage of the Apollo tapes at NASA Goddard — or any other NASA or NASA-utilized facility where they may have been shipped.

Technical spokesman for the group is Bill Wood, a retired Apollo tracking station engineer in Barstow, California. He supported all of the Apollo missions at Goldstone — part of NASA's worldwide network of deep space antennas run by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Wood hasn't been happy of late with some reports saying that they are looking for "missing Apollo videotapes" — as well as tabloid claims that NASA had somehow bungled a task.

"That's the furthest thing from the truth," Wood told SPACE.com. "There are no lost Apollo video tapes," he emphasized.

Never-before-seen view

For the last three or four years, the private group has been searching for special raw data recordings that contain unconverted slow-scan television (SSTV), recorded as a backup in case of an equipment glitch or a video circuit outage during the historic moon strolls of Armstrong and Aldrin.

Since there were no problems converting the slow-scan signals to National Television System Committee video standards, there was no need to use the backup telemetry recordings. Hundreds of boxes of Apollo-era magnetic tapes were subsequently shipped to NASA Goddard, later to be likely turned over to the National Record Center in Suitland, Maryland, Wood said.

Most of the Apollo tapes were later returned to NASA Goddard, including the raw Apollo 11 SSTV tapes. However, what happened to the tapes is not known. Because the SSTV was of superior quality to the scan-converted pictures broadcast out to the world at large, the hope is to recover them and give the public a higher-quality, never-before-seen view of the first human expedition sent to the Moon. Along with video, vintage Apollo 11 telemetry is also being sought.

Wood said he doubts the tapes have been trashed. On the other hand, there's a 50/50 chance they were recycled.

"Since telemetry recording tapes back then cost $90 to $100 a reel... well, that was back when $100 dollars was $100 dollars," Wood said. A magnetic rehab center at Goddard, he said, may have wiped the tapes clean — a budget-saving measure for reuse of the recording tapes.

"What we're hoping, though, is that somebody, maybe, might have saved some of them," Wood added. "We want to interest people to see something better than it happened at the time."

Range of formats

Meanwhile, at the Goddard Space Flight Center, the search is on.

"Hopefully, if we can find one set of tapes we can find them all," said Dave Williams of the National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC) at the NASA field center. "We still have some possibilities we're looking into, so I'd say the tapes might be found and depending on how they have been stored may well be readable," he told SPACE.com.

Williams and several colleagues are engaged in the Lunar Data Project — a different effort to take relevant, scientifically important Apollo data archived at NSSDC — analog data, microfilm, microfiche, photographic film, or hard copy documents and digitize that range of formats.

If the data were more readily available and usable in today's data rich and readable world, restoring Apollo data could provide a wealth of information for scientific studies and planning for future lunar exploration.

Migration of data

"There's a lot of old data that we don't seem to have," suggested Philip Stooke, Associate Professor at the University of Western Ontario's Department of Geography in London, Ontario, Canada. "I think more Apollo-era science data is missing too."

Hard at work on an atlas of lunar exploration, Stooke told SPACE.com that he was personally looking for images of the Moon taken by Explorer 49, a NASA radio astronomy mission that settled into lunar orbit in 1973. The probe carried a panoramic camera to monitor the deployment of its booms.

"It seems that the science data were preserved... but not those images," Stooke said.

The entire lunar data hide and seek saga that's alive and well here in the U.S. is being repeated in Russia too. "I work with people in Moscow who are trying to recover old lunar data," Stooke added.

The worry that old Apollo tapes can deteriorate is a valid concern, Stooke said. "Migration of data to new media is essential in digital archiving... and it's an ongoing problem."

What about the CD-ROMs of today? Are they going to be readable in 50 years?

"Don't count on it," Stooke responded.

For details regarding the search for the Apollo 11 Slow-Scan Television Tapes, cast your eyes on these sites:

|

|

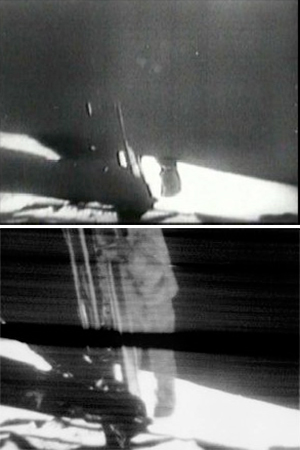

A Polaroid of a slow-scan image taken at the Goldstone tracking station reveals far more detail than publicly broadcast TV during Apollo 11 moonwalk. A search is underway to locate old Apollo tapes and freshen them up with digital technologies. (Bill Wood)

Scan-converted broadcast image of Neil Armstrong descending the lunar module ladder taken at the Goldstone tracking station. This was the image the world saw of the first human on the moon. But a Polaroid picture of the slow-scan television image reveals greater detail. (John Sarkissian/CSIRO Parkes Radio Observatory) |