December 23, 2008 — Orbiting the moon 40 years ago on Christmas Eve, 1968, Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders snapped a picture that would become an icon of the 20th century: Earth, rising beyond the Moon's barren and bleached horizon into the blackness of space. To Anders and his crewmates, Frank Borman and Jim Lovell, the loveliness of their home world was magnified by its smallness; from almost a quarter-million miles away, they could hide it behind an outstretched thumb.

And yet, as Anders later said, in going to the Moon they had barely left home.

Forty years later that famous Earthrise photo seems like a relic from a bygone era, when the space program was about going somewhere. Apollo's "giant leap for mankind" revealed scientific treasures only the Moon possesses, gave us a priceless new perspective on our own world, and showed us that when we work together, we can achieve seemingly impossible things.

But no one has been back to the Moon, or anywhere else beyond low Earth orbit, since 1972. And even now, almost five years after the White House put a lunar return on NASA's agenda, no one can say when humans will again see their planet suspended over the Moon's ancient and pristine expanse — or when they venture even farther into space, to the rusted deserts of Mars.

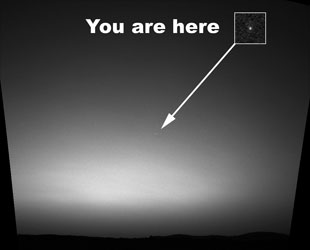

Meanwhile two of our robotic avatars — the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity — have roamed the Red Planet, photographing its alien landscapes and probing its secrets. Already, they have helped to show that over much of Mars conditions were once favorable for life. Through their electronic eyes we have even looked homeward, as Spirit did in March 2004, when it photographed Earth as a bright dot in the predawn Martian sky.

Earth over Mars as photographed by the Spirit rover (NASA) |

To me, that picture symbolizes the daunting challenges that we must solve before we can send humans to Mars. There are the medical hazards of space radiation and the psychological effects of being so far from home that realtime conversation with Earth is impossible, due to the minutes-long travel time needed for radio signals to cross the vast interplanetary gulf. There is the need for systems more reliable than any yet created for human spaceflight.

And there is even the basic question of how to land on Mars. The problem is the Martian atmosphere, which is too thin to provide much help in slowing down, but just thick enough to pose serious difficulties for a spacecraft large enough to carry people, hurtling toward the surface at interplanetary speeds. For now, experts say, even if we could send astronauts to Mars, getting them down safely is beyond our capability. But then, so was going to the Moon, less than a decade before we made it happen.

Mars is an Everest for humanity, but the lesson of Apollo is that we will climb it when we decide to. The challenges of Martian voyages, and the others that await us on our endless journey into the cosmos, will be solved with the same kind of ingenuity and passion that created Spirit and Opportunity.

During their development the engineers and scientists working on the rovers had to overcome one technical showstopper after another. Even after the rovers arrived safely on Mars in January 2004 they faced a slew of crises, from an overloaded computer memory that put Spirit into a temporary coma, to the sand dune that halted Opportunity's trek for six long weeks. In the end, all the problems were overcome — and then some. The rovers were designed to last 90 days, and yet today, almost five years after reaching Mars, they are still exploring.

But there is one thing these incredible machines will never do. Spirit and Opportunity will never come home and describe their Martian adventures. They will never tell us what it was like to have that mind-boggling view of Earth, having made the next giant leap toward the stars. But already, they've given us a message that, if we heed it, will take us farther than we can imagine.

It's the unspoken message in every transmission from our robotic surrogates: Follow me.

Science journalist and space historian Andrew Chaikin is the author of A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. His latest book is A Passion for Mars: Intrepid Explorers of the Red Planet. For more information visit his website.