October 8, 2013 — If Google Maps existed back in 1969 and included directions for navigating to the surface of the moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin might have plugged in "Tranquility Base" and been told to begin their descent by passing over "Mount Marilyn" on their way to mankind's first lunar landing.

Entering today a search on the real Google Moon website turns up no lunar features named "Mount Marilyn." It does however, find "Montes Secchi," the label later assigned to the same lunar mountain by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

"You can google 'Mount Marilyn' you know," James Lovell, who piloted the first manned spacecraft to circle the moon and later commanded Apollo 13, told collectSPACE.com, in reference to the overall search engine. "But it was never officially recognized by the IAU."

But should it have? Lovell, and his Apollo 8 crewmate Bill Anders, both recently went public with their desire to see the IAU recognize some of the craters and lunar landmark monikers they first coined more than 40 years ago. Letters by the two astronauts about the oversight were published by New Scientist magazine in September.

Apollo 8 crew members Frank Borman (left), Bill Anders and Jim Lovell, posing outside their command module. (NASA) |

"I don't want to make it a big issue but I would like to have some type of formal statement from the IAU saying, 'Yes, we understand that you have adopted or named this little triangular mountain Mount Marilyn and we see there is no reason why it shouldn't officially be called that,'" remarked Lovell.

In defense of Mount Marilyn

Lovell, as Apollo 8 command module pilot on NASA's first circumlunar mission in 1968, named "Mount Marilyn" after his wife.

"It was strictly my idea," he said. "I examined the surface [charts] very carefully before we took off, looking at all the craters and tried to get an idea, before being so close to them, how I could give some idea as to what I was looking at as we were going around [the moon]."

Lovell knew his Apollo spacecraft's path orbiting the moon would be similar for the flights that followed, including the first mission to land there. So, having easily-remembered surface feature names, like "Mount Marilyn," would be of use not just to Apollo 8, but to future voyages as well.

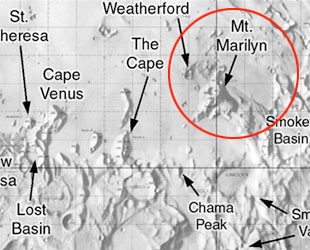

Map showing the location of "Mount Marilyn" and other astronaut-labeled lunar landmarks for Apollo 10. (LPOD/Phil Stooke) |

"It was a sort of an informal name but we kept it up and it took hold," Lovell told collectSPACE. "The Apollo 10 crew used it for their descent in testing the abort phase of the flight. Apollo 11 used 'Mount Marilyn' as the point [where] they started to go in to their landing site. And that was the intent of it."

The rise of Montes Secchi

So how did Mount Marilyn, which is located just inside the "shoreline" of the Sea of Tranquility, come to be "Montes Secchi" instead?

"Admittedly, I did not make a formal request to the IAU to name it," said Lovell. "I never thought I was in the position to ask them to do that."

And so it came down to a string of craters.

"North of Mount Marilyn, there is a fairly large crater called Secchi and outgoing from there are a lot of small craters," Lovell said. "So, they named those craters Secchi Alpha, Secchi Beta, Secchi Gamma... and on this little triangular mountain, on one end of it, is a little crater called Secchi Theta."

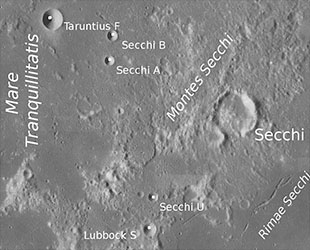

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) image of the Secchi craters and Montes Secci, as assigned designations by the IAU. (NASA) |

But at the time Apollo 8 orbited the moon the mountain did not have a name.

"It didn't have a name before, but there was a contest later on and it became 'Montes Secchi,' because the little crater was on there," Lovell said.

A mount (or crater) by any other name, or location

Lovell's "Mount Marilyn" might come across as colloquial compared to "Montes Secchi," but other lunar landmarks have modern namesakes.

In fact, there are three craters on the far side of the moon named "Anders," "Borman" and "Lovell" in honor of Apollo 8's crew. Only they aren't the craters the crew named for themselves.

"In training [for Apollo 8], I chose names for a few of the unnamed craters along our orbital track," Anders wrote to New Scientist. "I had picked a small but well-formed crater just over the lunar horizon to be 'Anders,' since it could not be seen from Earth and thus had not been named by early moon gazers."

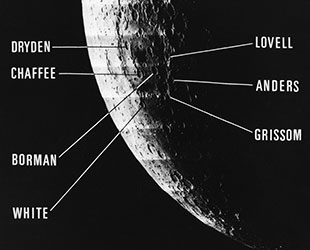

The moon's far side, with labels identify the craters named by the IAU for the Apollo 1 and Apollo 8 crew members. (NASA) |

The IAU however, thought differently. It did name a crater "Anders," just not the one the Apollo 8 crew member had picked out, a change the astronaut protested in a letter he sent to the union. He even included his flight map showing his preferred 'Anders' crater.

"I got brushed off by its bureaucracy," Anders explained to New Scientist, "and never got my map back."

Stuck between the moon and the IAU

According to New Scientist, which contacted the IAU for comment, the union was unaware of the "controversy."

Lovell told collectSPACE he has not heard from the union since his letter went public, but he is considering initiating contact.

"It would be nice for me to put in an application to formally ask the IAU to recognize [Mount Marilyn]," he said.

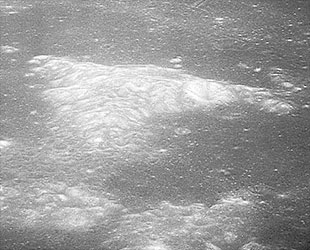

Apollo 10 photograph of the surface of the moon showing "Mount Marilyn" near the Sea of Tranquility. (NASA/McMahan Photo) |

To Lovell, it's a matter of staying consistent with terrestrial and extraterrestrial precedent, when explorers have given names to their discoveries.

"If it hasn't been pre-named or if it isn't well recognized by a name, then it should be named by the people who see it, who recognize it and who have things to do with it," Lovell commented. "Since [Mount Marilyn] entered the lexicon of the Apollo missions, it should have official recognition."

The International Astronomical Union states on its website that it has been the world's official arbiter of planetary and satellite naming since its inception in 1919.

"The IAU does not consider itself as having a monopoly on the naming of celestial objects — anyone can in theory adopt names the way they choose," union officials stated as part of a general policy document. "However, given the publicity and emotional investment associated with these discoveries, worldwide recognition is important."

In August, the IAU began accepting public suggestions for newly discovered celestial bodies. The policy however, did not apply to renaming objects already designated.