advertisements advertisements

|

|

Jack Garman, NASA engineer who 'saved' Apollo 11 from alarms, dies

September 20, 2016 — John "Jack" Garman, a NASA engineer whose knowledge of the computer aboard Apollo 11 saved the historic first lunar landing from a last-minute abort, died on Tuesday (Sept. 20). He was 72.

Garman's death came after a several year battle with bone marrow cancer, according to an email by his wife that was forwarded to the Johnson Space Center retiree community and then shared with collectSPACE.

"Sad to hear of the passing of Jack Garman," Wayne Hale, a former flight director and shuttle program manager, wrote on Twitter on Tuesday. "He saved the first moon landing, in case you didn't know."

On July 20, 1969, as astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended to the moon's surface aboard the Apollo 11 lunar module "Eagle," a master alarm rang out signaling a problem with the guidance computer.

"Master caution and warning is like having a fire alarm go off in a closet, okay?" Garman described in a 2001 NASA oral history. "I mean, 'I want to make sure you're awake' — one of these [alarms] in the earphones, lights, everything. I gather their heart rates went way up and everything."

With just seven and a half minutes remaining before they were set to touch down on the moon, Armstrong and Aldrin reported a program alarm. "It's a 1202."

It was not an alarm that they had seen in their training.

It was however, one that Steve Bales, the guidance officer in Houston Mission Control, had encountered during a late simulation, and more importantly, it was one that Garman had helped to trigger.

"I clearly recall helping [the trainers] come up with a couple of semi-fatal computer errors, errors that would cause the computers to start restarts," Garman recalled. "Well, it was one of those or a derivation of one of those."

"It was just a few months before Apollo 11 ... that a young fellow named Steve Bales, a couple years older than I was the guidance officer, and [who] was the front-room position that we most often supported because he kind of watched the computers," Garman continued. "One of these screwy computers alarms, 'computer gone wrong' kind of things, happened, and he called an abort of the [simulated] lunar landing and should not have, and it scared everybody to death."

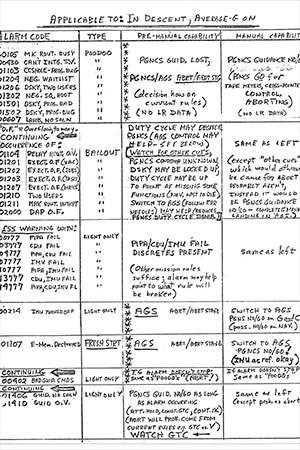

In response, flight director Gene Kranz insisted Bales write down every alarm that could possibly go off. Bales, in turn, gave the assignment to Garman.

"I still have a copy of it," Garman told NASA in 2001. "It's handwritten, under a piece of plastic, and we wrote it down for every single computer run and stuck it under the glass on the console."

Of course, Armstrong and Aldrin didn't know that.

"They're the first people [about] to land on the moon, and one of these computer alarms come up, they get this four-digit code for what the alarm is — 1201, 1202 were the two alarms, as I recall," said Garman.

"The only reason I remember that is a couple of my friends gave me a t-shirt that had those two alarms on it when I retired," he admitted.

With every passing second, the Eagle was growing closer to the moon, and so time was of the essence. Bales called to the back room, "1202. What's that?"

Garman consulted his list. The 1202 alarm indicated that the guidance computer was being overloaded with tasks. It was having trouble completing its work in the cycling time available.

"We looked down at the list at that alarm, and, yes, right, if it doesn't reoccur too often, we're fine," reported Garman.

"Give us a reading on the 1202 program alarm," Armstrong radioed, with a bit more urgency in his voice.

"We're go on that, Flight," Bales advised Kranz. Before the flight director could respond, capcom Charlie Duke relayed the news to the crew, "We're 'Go' on that alarm."

The alarms were not over, though. Less than minute later, there was another 1202 alarm, followed by three more — a 1201 and two 1202 alarms — in under 40 seconds.

"When it occurred again [it was] a different alarm but it was the same type," Garman recounted. "I remember distinctly yelling — by this time yelling, you know, in the loop here — "Same type!" and [Bale] yells "Same type!" I could hear my voice echoing. Then [Duke] says, "Same type!"

"Boom, boom, boom, going up. It was pretty funny."

It was later that Garman recognized the significance of that moment.

"You don't realize until years later, actually, how doing the wrong thing at the right time could have changed history. I mean, if Steve had called an abort, they might well have aborted," he stated. "In retrospect, [that was] one of those points where you were right at the — you were a witness in the middle of something that could have really changed how things went."

John R. Garman was born in Oak Park, Illinois, on Sept. 11, 1944. He attended the University of Michigan, earning a bachelor of science in engineering physics in 1966, the same year he began working for NASA's Johnson Space Center as director of flight operations for mission planning and analysis in the flight support division.

At the time Apollo 11 encountered the alarms, Garman had advanced to lead the program support group for guidance software in the flight software branch.

Garman continued moving to more responsible positions, supporting the development of the software for the space shuttle, until he was appointed the deputy director of the mission support directorate in 1986. The following year, he reported to NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. to be the director of information systems services in the space station program office.

Garman returned to Johnson Space Center in 1988, where he advanced to chief information officer until his retirement from NASA in 2000. He then joined the OAO Corporation, which was later acquired by Lockheed Martin, serving as a technical director for NASA services, before his retirement in 2010 to consult in software engineering and information technology.

For his service to the program, Garman was honored with numerous NASA awards, including two exceptional service medals. In 1970, Garman was part of the Apollo 13 team awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Richard Nixon.

Garman was married to the former Susan Hallmark of Los Angeles and had two daughters. |

|

Jack Garman was working in a back room of Mission Control when alarms aboard Apollo 11 threatened to abort the first lunar landing. His quick work gave the "go" for the mission to continue. (NASA)

Example of the Apollo lunar module display and keyboard (DSKY) like what lit up with 1201/1202 alarms on Apollo 11. (Smithsonian)

Jack Garman's "cheat sheet" listing the Apollo computer alarms.

Jack Garman (second from left) is seen at his console in a support room for the guidance computer in Mission Control. (NASA)

Jack Garman (left) accepts an award from astronaut Alan Shepard. NASA deputy administrator George Low in middle. (NASA) |

|

© 1999-2025 collectSPACE. All rights reserved.

|

|

|

|