July 17, 2019 — Fifty years later, Michael Collins only has vague recollections of where he was when he first saw humans land on the moon.

He knows very well where he was when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the lunar surface on July 20, 1969; he just does not recall the specifics of when he was finally able to watch a playback of humanity's first exploration of the moon.

Of course, at the time the moon landing was happening, Collins had both the best and worst seat in the house, so to speak. On the one hand, he was only 60 miles (96 kilometers) above the moon. As command module pilot, Collins stayed in lunar orbit as his Apollo 11 crewmates, Armstrong and Aldrin, descended to Tranquility Base.

But on the other hand, as capable as his ship, Columbia, was, it lacked a TV. And so Collins had no means of watching what his two crewmates were doing below.

"I guess if somehow I could have seen them descending, I'd loved to have seen the lunar module land. I'd liked to have seen how it looked out the window as the craters went roaring by and as they got closer and closer, the dust started kicking up. All of those things, I'd loved to have watched that, but the technology wasn't there," Collins said in an interview with collectSPACE.

"I would like to see the Easter bunny hopping around too, but you have to get real about what is possible," he said with a laugh.

What Collins does vividly recall is seeing the photographs that his two crewmates took while on the moon.

"The thing that I can remember that impressed me was the clarity," he said. "That 70mm Hasselblad camera told the truth so viscerally, so dramatically. And the clarity of it — I mean there's no atmosphere, obviously, on the moon, so you know that before you look at the pictures, but the beauty, the detail, the magnificence of the photography, that was just a surreal look to me and I was just surprised that it was so vivid and so clear."

Far from lonely

Collins circled the moon 12 times during the 21 hours that Armstrong and Aldrin were on the lunar surface. He completed two more orbits before the lunar module Eagle re-docked and the three crewmates were reunited.

"Not since Adam has any human known such solitude as Mike Collins is experiencing during this 47 minutes of each lunar revolution when he's behind the moon with no one to talk to except his tape recorder aboard Columbia," stated a NASA commentator in Mission Control during the flight.

"That's baloney," said Collins 50 years later. "You put some Samoan on his little canoe out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean at night and he doesn't really know where he's going, he doesn't know how to get there. He can see the stars, they're his only friend out there, and he's not talking to anybody. That guy is lonely."

"I didn't experience that kind of loneliness," he said. "So I did not have Mission Control yakking at me for a full two-hour orbit — for 40 minutes or so I was over there behind the moon — but I was in my comfortable little home. Columbia was a nice, secure, safe, commodious place. I had hot coffee, I had music if I wanted it, I had nice views out the window."

"To depict me as in despair or something and so lonely as in, 'Oh my gosh, I could hardly wait to get back to the human voice coming directly up from Earth,' yeah, that's baloney."

An unordinary success

Beyond that though, Collins feels people have him "pegged properly."

"I was one-third of a very unusual enterprise, but it was pretty clearly delineated. Perhaps the focus on my time alone behind the moon was a good natured attempt on the part of observers to build something more dramatic into that," he told collectSPACE. "I'm making it sound like a very ordinary kind of a thing. It wasn't ordinary, but neither was it otherworldish, in a more dramatic sense."

The mission however, could have been much more dramatic, said Collins. The thing that still stands out to him after 50 years is how everything came together to work as planned.

"The primary thing in my mind, that of a test pilot, is 'Holy mackerel, nothing went wrong!' That's unusual; all those little bits and pieces — pieces of machinery here, that little bit of it up over there — all the things that could have gone wrong. The flight to the moon and back is a long and fragile daisy chain. Any tiny break in the chain and and the whole venture is screwed," Collins described.

"I just couldn't believe that our equipment, down to the last little nut and bolt, that there wasn't something, somewhere in it that had been overlooked, something that was going to malfunction and when it went wrong, something we might or might not be able to cope with."

"So I salute the designers, engineers, the mechanics and the maintenance people, all of them who made that equipment so reliable," he said.

Memories of the moon

Despite the renewed attention raised by the mission's 50th anniversary, Collins feels that most of the public today does not give much thought to Apollo 11, and that is not necessarily a bad thing.

"I think the mission still resonates with those who are interested in space and we have these vivid recollections, but I don't think the average person does," said Collins. "They've got a lot of things that to them are a hell of a lot more important than worrying about when those guys went to the moon, or what it looked like, or what it means today. They go on about their business."

"So I think we place too much importance on it. I mean, we imagine people know about it, or could think more about it, or consider it more important or more valid, a thing to worry about, but they have other lives to live," he said.

As for himself, Collins does not place a lot of significance on this being the 50th anniversary of his mission to the moon.

"I realize that the number 5-0 is probably to some — perhaps to the people whose livelihood depends on recording these things — probably 50 is a lot better than 49 or 51, but not to me," he said. "To me it's the clarity of my memory, which gets clouded as time goes by, and to me, 50 is a little bit worse than 49, and 48, or, oh boy, 47 wasn't so bad."

"So no, I don't, derive any special feeling from this particular anniversary," said Collins. |

|

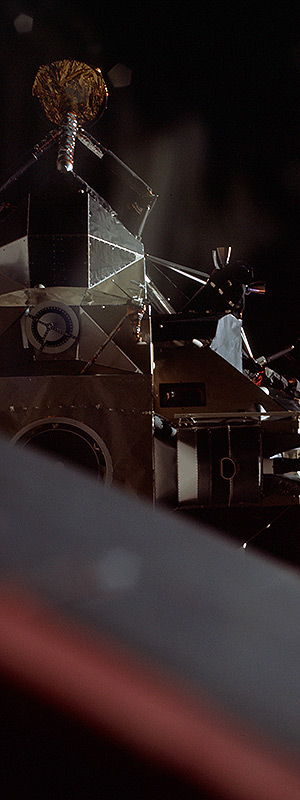

Michael Collins' view from aboard the Apollo 11 command module Columbia as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin depart on board the lunar module Eagle to make the first landing on the moon. (NASA)

Michael Collins is seen aboard the command module Columbia on the first day of the Apollo 11 mission, July 16, 1969, while in transit to the moon for the first lunar landing. (NASA) |