April 13, 2010 — Tuesday marks the 40th anniversary of the in-flight emergency onboard Apollo 13. With the call to Mission Control, "Houston, we've had a problem," the goal for the astronauts and flight controllers went from landing men on the Moon to bringing them safely back to Earth.

To mark the flight's four decades, author Andrew Chaikin shares the crew's insights into their "successful failure."

I spent eight years interviewing 23 of the 24 Apollo lunar astronauts for my 1994 book "A Man on the Moon" (Apollo 13's Jack Swigert had died a few years before I began my research.) When I revisited those amazing conversations for my book with Victoria Kohl, "Voices from the Moon," I was struck by how many surprises came through in the astronauts' words. And none were more memorable than the comments of Apollo 13 commander Jim Lovell and his lunar module pilot, Fred Haise.

For starters, Jim Lovell told me that he did not regret the way Apollo 13 turned out — despite the fact that the explosion of an oxygen tank 200,000 miles from home cost him his chance to land on the moon, and almost cost him his life.

"We were given the situation," Lovell explained, "to really exercise our skills, and our talents to take a situation which was almost certainly catastrophic, and come home safely. That's why I thought that 13, of all the flights -- including [Apollo] 11 -- that 13 exemplified a real test pilot's flight."

But Fred Haise revealed different feelings. "Our mission was a failure," he said. "I mean, there was no way around it. There's no question it was a remarkable recovery from a bad situation. But at the same time, relative to the mission intended, it was a failure."

"The biggest emotion I had for several months after that flight was disappointment," said Haise. "It was the biggest emotion in real time, when the explosion happened, was disappointment. Just a big sinking feeling..."

"Biggest disappointment of my life."

Apollo 13 lunar module pilot Fred Haise peers out of the Aquarius lunar module's window. (NASA/Andrew Chaikin) |

Actually, Haise said, the trauma of Apollo 13 began even before liftoff, when crewmate Ken Mattingly was bumped from the flight because of a suspected case of German Measles and replaced with backup Jack Swigert. "The crew change-out was in itself emotional," said Haise. "You had a team, you had worked together for a long period, and now at the last minute you're going to partially take the team apart."

What the astronauts could not have known, of course, was that far greater stresses awaited them in space. But as Haise recalled, the accident aboard Apollo 13 had a different feeling from any emergency he'd experienced flying high-performance jets.

"Most of the serious things I've had [in airplanes] were so quick that it was, frankly, only after the fact that, you've done whatever you've done, now you have time to even recollect and think about how bad it was. This, in comparison, was a slower moving drama than any close midairs or several crashes I've had in airplanes. Nothing like that at all."

Indeed, after the explosion, the astronauts had to endure a four-day ordeal as they struggled to reach Earth -- with the help of literally thousands of flight controllers, engineers, and NASA managers across the country, who worked around the clock to devise the necessary procedures for the astronauts' safe return. Still, Lovell said, he and his crew had plenty of problems no one on Earth could help them solve -- especially learning to fly the spacecraft in a way they had never trained for.

"You flew by the seat of your pants," Lovell recalled. "I mean, there was a case where you had to do your burns manually. You had to learn to fly the vehicle over again."

And then there were untried procedures.

"A lot of the instructions on what to do came from the ground, obviously. Because they had all the people -- the contractor people, the government people, the simulators -- to check out those things. But to execute them -- it's one thing to set up procedures and do it, but to execute them when you know that your ass is on the line is a little bit different. And that is essentially what was happening on Apollo 13."

Surprisingly, Lovell never felt as if he were staring death in the face.

"I think that as long as we had an option, it never really came up," Lovell explained. "If there was a chance to get home, you work on the plus side; you don't work on the minus side."

"I never felt we were in a hopeless [situation]," Haise agreed. "No, we never had that emotion at all. We never were with our backs to the wall, where there was no more ideas, or nothing else to try, or no possible solution. That never came."

Haise elaborated, "If we had tried to activate the LM [lunar module], and it would not have activated, then we'd have been [out of luck]. Or I'd turned on the LM and there would have been nothin', no [cooling] water [for the electronics], all the water tanks had burst, right then I'd have known, 'We ain't gonna make it.' But we had nothing like that ever occur."

"You understand what I'm saying?" Haise clarified. "There was nothing there that said irrefutably we don't have a chance."

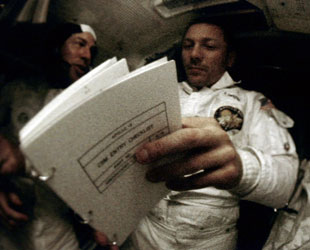

Apollo 13's James Lovell (left) and Jack Swigert (right) review an entry checklist for their return to Earth. (NASA/A. Chaikin) |

But what if things had gone differently? How would the astronauts have faced the certainty of becoming the first humans to die in space?

"We never would've thought about it until all hope was lost," Lovell told me. "And then our idea was, if all hope was lost, if we went by the Earth — say we missed the Earth. And we were on an orbit about the sun, if we had exceeded the escape velocity.... My idea was to hold off, you know, as long as we had options, as long as we could stand it, send back data.... We probably would have been farther out than anybody. And then, you know, then we would decide, you know, what to do.

"People often say, 'Did you [carry] a suicide pill?' or something like that," said Lovell. "You didn't [need] those. All you had to do was crank open the little valve to the hatch, there...

"Maybe we would have all committed suicide by opening up the vent valve," said Lovell. "And that would have been the end of the deal."

Science journalist and space historian Andrew Chaikin is the author of "A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts" and "Voices from the Moon: Apollo Astronauts Describe Their Lunar Experiences." For more information visit his website.