February 5, 2018 — Michael Leinbach didn't want the book to be about him.

A key leader in NASA's efforts to recover from the loss of space shuttle Columbia on Feb. 1, 2003, Leinbach knew the story of the accident's aftermath was bigger than just him. He was not aware, though, just how much larger it really was.

"When I say I did not appreciate it, that is really true. I did not appreciate what all of those people did for us out in Texas to get the debris, which I then in turn, was responsible for reconstructing to figure out what happened," he says.

"All of those people" ultimately numbered more than 25,000, representing federal, state, county and local government authorities, in addition to volunteers, many of whom who were living in the areas when the shuttle fell. Together, they combed an area about the size of Rhode Island, searching for the astronauts' remains and the remnants of the fallen winged orbiter.

It was the largest ground search in U.S. history, and until Leinbach decided to put it into print, it went largely untold.

"I personally hate the thought of the book 'written by Mike Leinbach.' I would like it to be, 'Yeah, I contributed to it, just like everybody else did,'" he says.

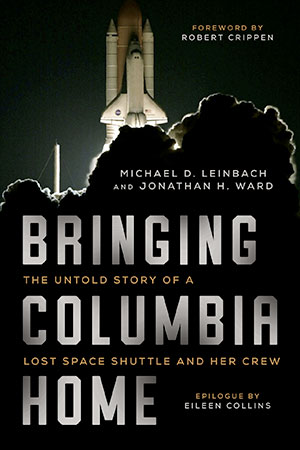

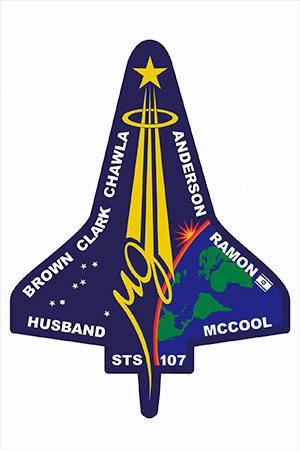

Leinbach, who as NASA's launch director gave the go for the STS-107 mission to lift off 16 days before tragedy struck on re-entry, shares his part, and many others, in "Bringing Columbia Home: The Untold Story of a Lost Space Shuttle and Her Crew" (Arcade Publishing), out now.

collectSPACE spoke with Leinbach, and his co-author Jonathan Ward, about their book, their research into the recovery, and what they hope people take away from reading about it 15 years later.

collectSPACE (cS): Mike, you say you did not want the book to solely be about you. Did you know that from the start or how did it grow from your own story to a collection of many people's stories?

Michael Leinbach: "When Jonathan and I first got together, it was going to be more Florida-centric — some recovery, some reconstruction, and I guess I will say, more from my perspective. But as soon as we got into it, we realized that there was a huge story out in Texas that I frankly did not appreciate. So, we expanded very quickly into telling the whole story.

"After 12 days [working in Texas in the wake of the accident], I came back to Florida to lead the reconstruction. I was kind of compartmentalized into that piece, not appreciating what it took to get us the debris. It turns out that was a significant portion of the book, and the story — the 25,000 people that ended up helping us walk that enormous area out there. I knew that it was happening of course, but I did not appreciate the depth of the effort, physically and emotionally out there."

cS: "Bringing Columbia Home" recounts four connected, but separate efforts: the search to recover the astronauts' remains, the search to recover the debris from Columbia, the reconstruction of the debris and what became of the debris after the investigation was concluded. Was it a challenge to include "the whole story" within the 400 pages of the book?

Jonathan Ward: "That, to me, was the question; how to put this into a form that was comprehensible when there are so many different moving pieces involved, so many people and so many different locations. This, to me, was a real kind of test of being a writer. How do you convey the excitement and the sense of chaos and that it all came together?"

cS: You were coming at this 15 years after the fact and yet you were able to tie down details to how many hours (and later specific days) certain things happened. What type of resources did you have to reconstruct the time line of the recovery and reconstruction?

Ward: "There were a number of stakes we could put into the ground.

"For example, Greg Cohrs, who was the U.S. Forest Service person responsible for organizing the crew searches in Sabine County in Texas, he kept a detailed diary of what he had been doing. He put that together in May 2003, right after the recovery ended.

"Mike also had a detailed set of notes of all of the meetings he went to during the course of the reconstruction and his time in setting up things in Barksdale. We had the Kennedy Space Center official chronology of what had gone on and we had the FEMA press releases that went out every day. So, there were some official stakes in the ground, too.

"But then going through and trying to organize... we had over 600,000 words of interview transcripts. Trying to piece those stories together from what people had remembered from 15 years ago and then hang those off of specific events was an interesting challenge and I think we did a good job in doing that."

cS: Given the sensitivities involved, was it necessary to wait 15 years for this book to be possible?

Leinbach: "I had started the outline for a book many years ago, maybe 10, 12 years ago, because I knew there was a story there. I didn't have the discipline to follow through. Plain and simple I didn't have the discipline to do it.

"But some of the people who have told their stories [in the book] had never told it before. For instance, we had a senior NASA official who was in charge of a lot of the activity out there... He had never told his story in public because it was still too raw for him.

"There are other people that said essentially the same thing; they never thought about telling, they never opened up before, because it was so raw.

"The fact that it took 15 years, you know there's a practical side to it, we were able to finish the space shuttle program. So, we were able to put that piece into the book, but I think if we tackled this story 5 or 10 years ago, like I originally started, I don't think it would have turned out like it did because people would not have been ready to tell their story. I really do believe that. I think the passage of time helped from that perspective.

"But we knew we had to get it done before too long. We knew we had a story that needed to be told and we needed to get on with doing it."

cS: Were there stories or details that you withheld due to the emotions they might evoke?

Leinbach: "Even with the passage of time, the wounds are still very deep. I think it is like talking to any veteran who knows of horrific times in a war. The passage of time makes it a little bit easier to talk about, but it may never completely heal."

Ward: "From the very outset, that was one of the first things Mike and I agreed on, this was not going to be a salacious book, this was not going to be a recounting of what the crew was going through during reentry. We weren't going to say anything more about the human remains recovery that had not already been published in official NASA publications. We said even less than had been released before.

"We wanted it to be emotionally real, but we also wanted to be respectful of the families and the people who were involved. You have got folks who are out there looking for their friends and looking for somebody else's loved ones and we did not want to do anything that was going to sensationalize that in any sense.

"That was our number one concern when we went to a publisher, to make sure that somebody understood that very clearly."

cS: As recounted in "Bringing Columbia Home," there were more than 25,000 people involved in the recovery and reconstruction. How did you limit yourselves to a subset of what could have been numerous more personal stories?

Leinbach: "We just kind of talked about getting a representative, a cross sample. We could have interviewed thousands of people and a lot of them would have been very personal stories, of course. They all would have been personal stories, some of them would have been sort of similar and so we kind of feel like we got a pretty good cross section.

"We didn't want to leave out any 'group types.'"

Ward: "We tried to do what I'd call in my organizational consulting work as doing a diagonal slice across the organization. We talked to a range of people, from those high up in NASA to people serving soup on the serving lines in the VFW hall. We were trying to get a cross section of everything that was going on.

"If I had any regrets in what we included, it is we didn't talk more about places like Nacogdoches and Corsicana and some of the other places that were farther west, who were just as impacted as the people of Sabine County at the far east end of the debris path. But that was where the crew recovery was, so that is where our concentration was.

"So I feel like I wish I had more time to talk with people in the western part of the debris path, but I think their stories would have been relatively similar to the ones we encountered."

cS: Did you encounter any reluctance on sharing this story?

Ward: "What surprised me was what we came up against when we were trying to find a publisher. People were saying, 'Well for one, it's space shuttle, people aren't as interested in the space shuttle as they are in Apollo,' or 'This isn't Challenger. Challenger was the exciting disaster, the one everybody remembers.'

"That, to me, strengthened our resolve that the Columbia story needed to be told. That to me is the huge important driver in this, that Columbia has been forgotten largely outside of the NASA community and the people of East Texas.

"The rest of America really doesn't remember Columbia. We need to remind them what went on, both to pay honor to the crew and also to all the people who came together when the country needed them and did what they needed to do."

Leinbach: "Half way through writing the book, we were talking with the publisher and between the publisher and Jon they convinced me to do this book in the first person.

"They convinced me that it would do better — not from a sales perspective, but that it would get it out to the public better. It would read better and therefore more people would read it and that's the intent, that more people know about this story.

"It's not my style, but that is the way it turned out. It's going to reach more people because I was convinced that more people would read it the way that it is rather than if it was in the third person."

cS: And if more people read it, what do you hope they take away from it?

Leinbach: "I hope people get out of this book that America is full of really, really good people and when we needed help they just stepped up and did anything we needed them to do. People in East Texas and Louisiana, and the firefighters from all across the nation came and helped us.

"We had over one hundred different agencies contribute from federal, state, local, volunteers — just everybody came together to do the right thing and there was no infighting, there was no us and them. Everybody was saying 'What do you need me to do? I'll go do it.' It was just America coming together when we needed help." |

|

Michael Leinbach, space shuttle launch director

Jonathan Ward and Michael Leinbach

Columbia recovery and reconstruction workers

STS-107 / Columbia mission insignia |