January 1, 2019 — NASA entered the new year with a new horizon, the farthest-ever encounter with a planetary object.

The agency's New Horizons probe, which in 2015 was the first to zip past Pluto, flew by the even more distant small world "Ultima Thule" (officially 2014 MU69) on New Year's Day (Tuesday, Jan. 1). It was the first close pass by a spacecraft of a Kuiper Belt object, one of the primordial building blocks of the planets in our solar system.

Mission managers and scientists, together with their family members and invited guests at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, joined in a New Year's Eve-style countdown to the flyby's closest approach, just 33 minutes after doing the same to welcome in 2019.

"5, 4, 3, 2, 1... go New Horizons!" exclaimed Alan Stern, principal investigator for the New Horizons mission. "Go New Horizons! Woohoo!"

Traveling at about 32,000 miles per hour (14 kilometers per second), the New Horizons probe came within about 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) of Ultima Thule (pronounced "Ultima Too-lee") at 12:33 a.m. EST (0533 GMT). The spacecraft, which is about the size and shape of a baby grand piano, was programmed to record science data and capture images of the city-size world, of which little was known about in advance.

"We hardly know anything about it, even after the three and a half years of chasing it down and studying it with the Hubble Space Telescope," said Stern at a pre-flyby press conference. "We have only been able to learn a few things about it. We know it is about 30 km [18 miles] in size. We know that it is red. We know its orbit very precisely."

"We don't know much else, other than it has an irregular shape. That is all going to change because New Horizons is bringing these amazing sensors there," he said.

The flyby, which took place at a distance of about 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion km) from Earth and about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) further out from the orbit of Pluto, took only seconds to complete, but New Horizons will need the next 20 months to transmit the seven gigabytes of data it was expected to collect at about 1,000 bits per second. Radio signals from the spacecraft take more than six hours to traverse the distance from the Kuiper Belt to Earth.

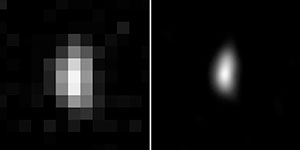

The first close images are expected to be released on Wednesday (Jan. 2). Prior to the flyby, the best that New Horizons' Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) was able to capture rendered Ultima Thule at only two pixels wide, which was an improvement over the single point of light that had been the only available view since Ultima was discovered in 2014.

New Horizons flew past Ultima Thule at an approach that was about three times closer than it had been to Pluto on July 14, 2005. Using its seven on board science instruments, New Horizons was pre-programmed to to collect geological, geophysical, compositional and plasma data on Ultima. It was also to search for any satellites (or moons), rings and atmosphere around the body.

The data may help answer some of scientists' key questions about the formation of planets, as well as the nature of "cold classical" Kuiper Belt objects that follow circular orbits in the same plane as the planets.

"We want to understand how objects like Ultima were assembled," Stern said. "There are two basic theories for how the building blocks for planets were assembled. In one case, you put objects together piece by piece. And then in the other theory, they are built by a hail storm of pebbles, boulders and other types of particles. Depending on whether we see a heterogeneous object or a monolithic object, we might be able to find out which of those theories is correct."

The New Horizons spacecraft launched from Earth on Jan. 19, 2006. Following its encounter with Pluto nine years later, the spacecraft was assigned the extended mission to explore the Kuiper Belt, study distant Kuiper Belt objects, heliospheric dust and plasma science as far out as 50 times the distance from Earth to the Sun through 2021.

New Horizons' flyby of Ultima Thule, history's first encounter with an object that was discovered after the mission to it began, continues a 60-year legacy of NASA pioneering space exploration.

"I think it is fitting that this flyby of Ultima Thule is at the interface of the 60th anniversary of [the launch of the first American satellite] Explorer 1 in 2018 and the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 [the first moon landing mission] in 2019. To me this milestone for New Horizons is full everything that NASA and NASA science is all about," Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's Associate Administrator for Science at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., wrote in an email to Stern.

"Fifty years ago, the first humans walked on a different world, the moon, as a result of NASA," said Stern. "And NASA was actually the first space agency to reach every planet in the solar system, from the closest planets, Venus and Mars, to the farthest, Pluto. And now we are out there going even farther." |

|

Artist's impression of NASA’s New Horizons probe encountering "Ultima Thule" (2014 MU69), a Kuiper Belt object that orbits one billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto, on Jan. 1, 2019. (NASA/JHU-APL/SwRI/Steve Gribben)

Mission scientists, their family members and invited guests cheer New Horizons' flyby of the Kuiper Belt Object "Ultima Thule" at 12:33 a.m. EST on Jan. 1, 2019 at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. (collectSPACE)

Just over 24 hours before its closest approach to Ultima Thule, the New Horizons spacecraft sent back images that begin to reveal the Kuiper Belt object's shape. The original images (at left) have a pixel size of 6 miles (10 km), not much smaller than Ultima’s estimated size of 20 miles (30 km), so Ultima is only about 3 pixels across. Image-sharpening techniques combining multiple images show that it is elongated (right panel). (NASA/JHU-APL/SwRI)

New Horizons Extended Mission logo. (NASA/JHU-APL/SwRI) |