|

|

|

|

Author

|

Topic: Another shuttle conspiracy book: "A Life in Space" (T. Furniss)

|

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-14-2007 09:38 AM

posted 08-14-2007 09:38 AM

I was really not done with Tim, but you made it easy for me. You proved my first point with him forcefully — Tim, you did not investigate the Challenger accident with me, or alone. You reported, and leave it at that. Now, I can finish my posts sooner than I had expected. Regarding FFrench evaluating "theories!" Equals evaluate "theories." quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

I think I'll leave it up to others here to decide whether querying the evidence for many of your and AbuTaha's theories is a discreditable thing to do.

I have three major objections, especially on the "many" and "theories." Where were you Tim? You had ten days and over a dozen posts to set the record straight. Why didn't you? You let FFrench go evaluate your "many theories." How many do you have? Do you know how many theories I had about the Challenger Accident? You used the expression, "AbuTaha's theories," in Flight and elsewhere. I am taking charge of my side. Here are my objections: - It is my opinion that the number of theories by Tim about the Challenger is zero. If he disagrees, then he should post his theories. A theory must be developed, and evaluated from every angle, i.e., get the extensive Commission Reports, textbooks, journals (not Flight International and tabloids), encyclopedia, get test results or do them, etc. Finally, the theory must be stated in clear, and error-free language. If Tim posts "theories" that fulfill the above requirements, I'll gladly participate in evaluating them. Tim encouraged FFrench to evaluate his and my theories. Is he crazy? He doesn't have theories. Conspiracy theories don't count. For my theories, see Item 3 below.

- The word "theory" brings to mind such greats as Newton and Einstein. Evaluating theories, like FFrench thinks he is doing now, conjures up images of a thinker probing the truth or falsehood of unique works. What's at issue is not the author(s), but the "theories" themselves. If I were FFrench, I assure Tim that I would take his name (Furniss), my name (AbuTaha) and "theories" and dump them in a garbage can. You're on your own, Tim. If McDonald and Hansen submitted proposals to study "AbuTaha's theories," they might get funds, from NASA or Thiokol, to study the "theories" and not "AbuTaha." But, if they submit proposals to study "AbuTaha as one of numerous sidewalk rocket scientists" (Robert Pearlman, 8356, by Hansen), then NASA and Thiokol wouldn't put up a penny for it. A tabloid might. What's magical is the word "theory," and you, Tim, allowed FFrench to bask in the glory of working on evaluating "theories." To FFrench: Evaluate Tim's theories; for mine, see next Item.

- Now, to the number of theories by me about the Challenger, which is also zero! The one thing that qualifies for a theory is the dynamic overshoot concept. I thought about it, but it does not conform to the strict requirements of a "new theory," and I let it go. Did I miss out on a great historic opportunity by not formulating a "theory" from my Challenger study? No. "Dynamic overshoot" is a serious engineering mistake (I still call it a blunder) and it should be corrected and taught at all levels. Someone in the Congress asked me a long time ago, "Did you invent the dynamic overshoot?" I answered, "No. God did." I never wrote that I had a theory about Challenger. If I change my mind, the theory will be examined by equals, and not here.

Then, what is this thread all about? mjanovec got it. quote:

Originally posted by mjanovec:

I suspect most people don't have the energy or will to read Ali's lengthy posts and then discuss/argue 100 different items simultaneously.

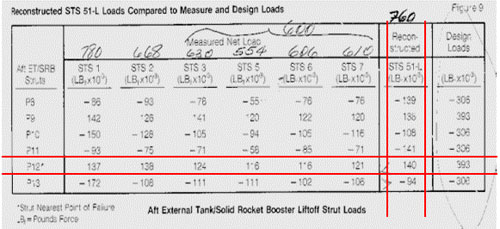

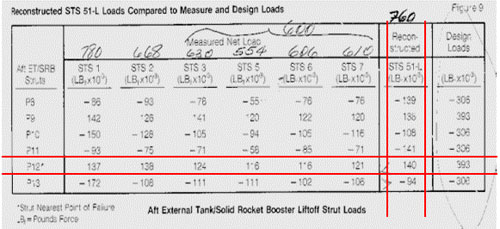

Make the 100, hundreds. That's it. This thread is about "Hundreds of Items" specifically identified by me. I define Item as a major mistake or a major observation. A major mistake is a blunder. I will give below two Items (out of hundreds): (1) one major engineering mistake and (2) one major observational error. And if you are the engineer (with capital E you claim), get your calculator ready, Scott.ITEM #1 (ENGINEERING MISTAKE)  If you were a kid when the Report of the Rogers Commission went on sale, you are off the hook. If you are not a technical person, you're also off. If you were an engineer or the like, you are not off the hook — post your comments. To Scott: You have come a long way since your degree, now you must participate. Look at the famous Table of loads in the struts of Challenger and previous missions from the Commission Report that I mentioned before. Forget my scribbles, a habit. Do you see the box where the red lines I added intersect? Can you read the number there? 140, i.e., 140,000 lb, or 140K. Do you see which Challenger Aft ET/SRB strut that was? P12* on the left. Do you see the footnote for that strut: It says, "Strut Nearest Point of Failure." Are we all oriented? Now, is that number correct because it appeared in a Presidential Commission Report or because the number was sanctioned by a VP? I want Scott to know that the number is so way off that I don't care who sanctioned it, including the VP Scott defends or applauds. That VP should have recognized the mistake then, in 1986. The 140K-force number is wrong. If I generated that number for the Commission, and then discovered the real value, I'd probably quit the damn profession altogether. In August 1986, I had a meeting set up with Admiral Richard Truly, then Associate Administrator for Space Flight at NASA HQ. Dick sent Astronaut Bonnie Dunbar to meet me instead. It was great meeting and talking with one of our astronauts. But there was business here, serious business. The 140K-force in the location of a failure that killed seven great astronauts is terribly wrong. To Bonnie's credit, she recognized that there was a problem of some sort. The next morning, she arranged for me to have a teleconference with some engineers at JSC. We kicked it around. We jabbed and punched — Scott. I am tempted to stop here and ask Scott, FFrench and the rest of you a specific question: What was the correct force in the strut nearest the point of failure on Challenger? Give me a number. And if you cannot provide the number, you are not entitled to make any snide remarks. I am going to push it further. I am telling you what is the problem; can you solve it? Robert politely pushed me: Give us answers, Ali don't give us questions. I will. But Tim should realize that saying he investigated Challenger with, or without, me is unacceptable. So, here is my Item #1: - The Commission was told the maximum force in the strut nearest the point of failure on Challenger was 140,000 lb.

- To me, this number is wrong. How did I know that? Like Scott, I knew the force the SSMEs produce at lift-off, 1.1 million lb. The 1.1MP is not the great deal, the great deal is how the 1.1MP get distributed in the struts.

- I found out from the JSC engineers that that strut was preloaded with 190K force.

- Then, the maximum load in the strut was 190K, and not 140K. That's about a 35% mistake. Impressed, Scott? Does anyone get the X% mistakes I have been throwing around? I give you the Shuttle's safety margins (these are standard nos), and then give you mistakes that exceed the safety margins. Is it registering anywhere? Where is Hansen, who posts:

Although I am not an engineer, I have studied and written about the history of engineering for approaching 30 years. At Auburn University, I also teach a course on the history of technological failure. I am not asking for your help here, Dr. Hansen, but do you teach your students that when the applied force exceeds the safety margins, the system is likely to fail? And let me say that my experience with "technological failures" is approaching 50 years, if quantity, and not quality, is the measure. - Here is the bombshell. The 140,000 lb force and the 190,000 lb force act in the same direction. Let me repeat that: The 140K and 190K forces act in the same direction. What was the maximum force experienced by the failed Strut P12 on Challenger — this is not only for the engineers, but also for everyone else? Did any of you lift one weight, and then lift two weights! I am really being smug here, and I hate it.

The 140K and 190K forces in the Challenger struts act in the same direction. The maximum force then was the sum of the two numbers, i.e., 140,000+190,000 = 330,000 lbs! You would have gotten an A+ on this one, Scott, FFrench, etc. The number in the Commission Table should have been 330,000 lbs. Let's test it. Then the boosters' field joints were tested under 330,000 lb force. The joint "opened and closed." Find it in one of my previous posts. The media went into frenzy. Everyone wrote about it (the 330,000 lb): Aviation Week, Washington Post, New York Times, etc. Tim Furniss says he also wrote about it. I am sure he did. Why didn't he scan it, do the above details and post it instead of wasting time with other messages? I know when Covault (Aviation Week), Sawyer (W. Post), etc. wrote about it, around Feb 87? None of them mentioned my analysis of the 330,000 lbs, though they knew about it. Did Tim mention it, with my name in Flight in 1987, not in the 1990s, when the issue became stale? If you did, Tim, post your Flight article.

ITEM #2 (OBSERVATIONAL MISTAKE)At T+40 seconds, Challenger made a sudden turn upward. How and how much? I am not going to entertain you with this one. I already did. Look it up in my Post #14 (I just looked it up. It's too long. No wonder some of you are bored). Here is a summary. Tim Furniss may have a theory or "many theories" about the Challenger accident. He should have mentioned the exact number of his theories to FFrench in advance. Conspiracy theories don't count. I trust FFrench will give him a fair hearing. I don't have any theories. Not even one. And if FFrench ascribes "theory" or "theories" to my name and write about them, it'll only be to showoff that he has undertaken the awesome responsibility of evaluating "theories." But I do have "hundreds" of "Items," as mjanovec noted and as I describe above with only two (out of many) Items, which FFrench is welcome to evaluate. Don't do it for my benefit. Do it for this thread. But I will be blunt, reference any major item you touch just as I had. Ali |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-14-2007 09:39 AM

posted 08-14-2007 09:39 AM

quote:

Originally posted by Robert Pearlman:

...if only I knew what it was you were talking about. Three examples of what?

I read the posts carefully, once, and I try to remember where things are at if I need them; I don't have time to reread. It was frustrating looking for the three things in, "Would you like to explain those three examples to me?"Thanks Robert. I thought my memory has been impaired. It's not, which is good. I stopped searching. I hope I haven't frustrated others with my posts.

Ali |

aurora

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-14-2007 10:39 AM

posted 08-14-2007 10:39 AM

OK Ali. I will rewrite my Chapter 10 and make it perfectly clear that it is what I reported for Flight with the information and data that you provided me freely for many years, including the times we met. You read Chapter 10 and cleared it after series of drafts were provided. I suggest you re-read the the final version of the Chapter 10 you cleared then send the modification to me and I will use it. I will also email you with this message. |

mercsim

Member Posts: 138

From: Phoenix, AZ

Registered: Feb 2007

|

posted 08-14-2007 11:40 AM

posted 08-14-2007 11:40 AM

This is so ridiculous. Robert, please allow Ali to start another thread about mis-informing engineering principles.The chart is labeled �Measured Net Load� look up the definition of what the words �measured� and �net� mean. Then you go on to show us you can add and tell us this is the number that should appear in a �measured� table. Wouldn�t that then be a �calculated� table? Look at the rest of the table! Particularly the titles! Then you compare apples to oranges. You are discussing loads in the strut and compare them with loads in a booster field joint. You are trying to compare two different things in two different places. What is the point of all this? The Commission found the accident was caused, in reverse order, by an explosion of the ET caused by the leakage (blow torch) of gasses from an SRB field joint. We all saw the photos and video and we all believe this to be true. Dynamic overshoot, apparent change in course, alleged overloaded strut joints, bla bla, bla bla, bla bla... Every time Ali presents evidence, he presents more questions, or mis-information than answers or explanations. Now we are into a sparring match between Tim and Ali. Maybe we�ll quit talking about pseudo engineering. Maybe Robert could move this into a new topic, or maybe we've come full circle and will talk about "Another shuttle conspiracy book..." Scott |

Moonwalker1954

Member Posts: 236

From: Montreal, Canada

Registered: Jul 2004

|

posted 08-14-2007 11:49 AM

posted 08-14-2007 11:49 AM

Robert, you're a very patient man. I would personnaly put a lock on that thread right away. It is not doing any good to any space enthousiast! Just my 2 cents.Pierre-Yves |

FFrench

Member Posts: 3093

From: San Diego

Registered: Feb 2002

|

posted 08-14-2007 12:11 PM

posted 08-14-2007 12:11 PM

quote:

Originally posted by Pierre-Yves:I would personally put a lock on that thread right away. It is not doing any good to any space enthusiast!

The thread has certainly taken a very interesting and new twist over the last couple of days, with the two most prominent public proponents of dynamic overshoot not able to agree with each other. For the space enthusiast, certainly this thread has probably become very wearing. For some space historians, it's probably extremely informative to read. I've learned a great deal about Furniss and AbuTaha and their work here, as well as how their very different personalities interact with their work. And should someone pick up the Springer-Praxis book or one the articles by Furniss and / or about AbuTaha in an old magazine article, read the 'dynamic overshoot' account of the Challenger launch, and want to go online to see what others say about its validity, this thread would tell them a great, great deal. |

aurora

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-14-2007 12:55 PM

posted 08-14-2007 12:55 PM

But you have not commented on the "smoking gun" Time Life story which you have in full and part of which was posted by me. Have you finished your review of my book and in it will you include the Time Life story or just ignore it? |

mjanovec

Member Posts: 3593

From: Midwest, USA

Registered: Jul 2005

|

posted 08-14-2007 10:21 PM

posted 08-14-2007 10:21 PM

quote:

Originally posted by Moonwalker1954:

Robert, you're a very patient man. I would personnaly put a lock on that thread right away. It is not doing any good to any space enthousiast! Just my 2 cents.

I disagree. I think this thread has been interesting with all of the twists and turns it has made. For the most part, discussions have been kept civil. For those who have an interest in this topic, I think it would be a dis-service to lock the thread. For those who have no interest in the topic, there is no obligation to read the posts. |

aurora

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-15-2007 02:21 AM

posted 08-15-2007 02:21 AM

By all means continue...BUT first comment on the "smoking gun" Time Life images story (ref nos provided) - pictures that I saw and reported about in Flight, with an artwork - and let's see French's review which will HAVE to mention the smoking gun.....I am sure that many people who have been logging on - and provided my website with incredible traffic (thank you) - would love to read it. There are other references to Challenger in the other chapters as the story unfolds. You have been reading just one chapter.Tim |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-15-2007 04:00 AM

posted 08-15-2007 04:00 AM

quote:

Originally posted by mercsim:

The chart is labeled "Measured Net Load" look up the definition of what the words "measured" and "net" mean.

And then? quote:

Originally posted by mercsim:

Then you go on to show us you can add and tell us this is the number that should appear in a "measured" table.

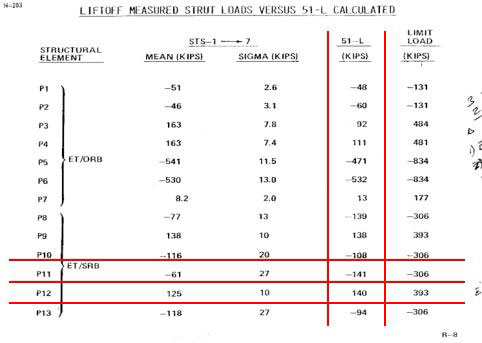

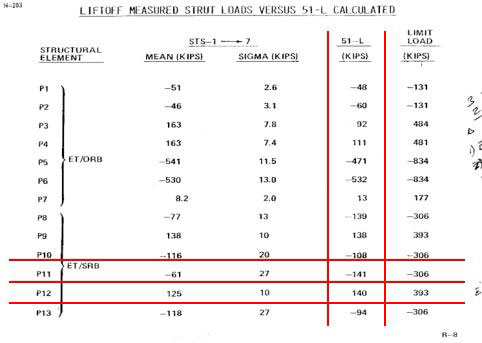

Perhaps, you impressed FFrench, but not me, mercsim. I don't mean to insult your technical abilities, but we have many non-engineers here. It is your responsibility, as an engineer and a citizen to help them understand the issues rather than let your emotions mislead them.The actual Table for the working Engineers is shown here. We don't need calculators. And look at this table, including "the titles," mercism. This was the Table shown to and discussed with the Commission in the Hearing of March 21, 1986. The Table is from Vol. V, p. 1353. This time I added one more red line. It is painful, but let me go through it again. Commissioner Kutyna asked about the loads in strut P11.  quote:

GENERAL KUTYNA: As you look at that load, however, this is in the area of that joint where possibly it failed. Would there have been any structural deformations as a result of that load that might have been a factor?NASA: It should not have, sir, with a 306 versus a 141 SR design and then the 1.4 times that. So that would be a big margin, really.

Suppose mercism or FFrench or any of you were in the shoes of NASA and the General asked that question, but about the strut in the area of the joint that failed on Challenger, Strut P12. What would you tell the Commission? Let me pit mercism with the General: quote:

GENERAL KUTYNA: Would there have been any structural deformations as a result of that load that might have been a factor?mercism: It should not have sir, with a 393 versus a 140 ... we're fat city.

If you calibrated and zeroed your instruments and measured 140,000 lb at Challenger liftoff, you should remember the 190,000 lb preload and ADD THE TWO NUMBERS. I don't want to spread more embarrassment than I did in the past, but I will give mercism one item. Someone thought the 140K and 190K numbers SUBTRACT and NOT ADD.NASA and Thiokol built a NEW test stand after the Challenger tragedy, and McDonald knows about it, to accommodate the 330,000 lb. Why did they build it if mercism's "Net Load" is only 140,000 lb? I bet Tim Furniss covered the test stand story as a reporter. And I bet Hansen read about it (not in Flight International, it was reported everywhere). McDonald should answer the question, why wasn't the 330,000 lb test stand built before Challenger, even before Columbia? The thrust, or the input force, remained the same over years. I finished my lengthy posts for this thread with the last one. I am ready. What's next Scott? Ali |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-15-2007 04:01 AM

posted 08-15-2007 04:01 AM

quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

I've learned a great deal about Furniss and AbuTaha and their work here

I am new to this thread, French, and I don't know "a great deal about" you. That's why I am eagerly awaiting your evaluations, especially, to know more about you. Do Tim's book alone and his Challenger Chapter 10 separately. Did my last post about "theories" discourage or intimidate you? If you only evaluate byzantine "theories," and not mere "mistakes and observations," then imagine my "dynamic overshoot" concept a "theory." You already have all the words that I would use to develop such a theory. quote:

Originally posted by French:

And should someone... want to go online to see what others say about its (dynamic overshoot) validity...

You can't wiggle your way out of this one French. You are committed. Reading your exchanges with Tim, I thought you were eagerly committed. I don't want to read what "others say." I know Henry Spencer's opinion. I want to read your sober evaluation of the "dynamic overshoot concept," as you see it in Tim's chapter 10 and in my previous posts. You have everything. I have no problem with your lowly opinion of my work (and me). But you still have a chance. You can rise or fall, not only in my eyes, but also in the eyes of others who may be curious to read your promised scholarly product.Of course, you can opt out. You can say you're not qualified scientifically and technically to do the scientific-technical evaluation. I don't know what you do, but I have no problem declaring instantly on this thread that I am not qualified to evaluate some of your work, if it is outside of my areas of expertise. Or, Robert can save you by pulling the plug. Ali |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-15-2007 04:01 AM

posted 08-15-2007 04:01 AM

quote:

Originally posted by Blackarrow:

I am in blood stepp'd in so far that, should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o'er.

I love this. It doesn't look that bad to me. I can already see dry and clear ahead.Ali |

FFrench

Member Posts: 3093

From: San Diego

Registered: Feb 2002

|

posted 08-15-2007 08:51 AM

posted 08-15-2007 08:51 AM

Oh boy. Now this is getting wearing. When requesting an independent, open-minded review, one generally does not then insist on what 'has' to be included in such a review or which chapters should be covered as separate reviews, etc... instead, you wait for the review. I'm still reading the work. I only recieved it last week. There is a great deal to comment on. And in the meantime, it seems most readers have been turned off by this thread and are no longer interested in an independent assessment of its contents - which makes perfect sense - it's getting tiresome. I'm beginning to feel the same way. |

Dwayne Day

Member Posts: 532

From:

Registered: Feb 2004

|

posted 08-15-2007 09:55 AM

posted 08-15-2007 09:55 AM

quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

Oh boy. Now this is getting wearing.

You haven't figured this out yet? It's a conspiracy theory book (see the title of the thread). Conspiracy theorists generally share common traits. Trying to reason with them is pointless. But if you want to try, I suggest engaging them in a spirited e-mail conversation. |

mercsim

Member Posts: 138

From: Phoenix, AZ

Registered: Feb 2007

|

posted 08-15-2007 10:34 AM

posted 08-15-2007 10:34 AM

� It is your responsibility, as an engineer and a citizen to help them understand the issues rather than let your emotions mislead them.�This couldn�t be further from the truth! My emotions have not mislead anyone! If I had any responsibility here it was to keep people like you from mis-informing others. I have merely attempted to point out your inconsistency in attempting to present facts in a very small sample of your work. I think the entire thread is full of mistakes. I have just refrained from speaking up. However, if I can point out your inconsistency or mistake in a simple example, maybe others will see you could have made mistakes in the rest of your posting. The fact in this example is you presented a table and talked about it. You talked about calculated loads and the table clearly said �measured�. This was just an easy spot for non-technical readers to see. You compared (or appeared to compare) a strut calculated number to an SRB field joint. One of those things we learned in engineering school, either present it properly with all the information or leave it alone. Then you present another chart in an attempt to clarify your position. It just adds more confusion. Then you challenge me by asking �what�s next� No matter what anyone says or presents, you will answer with more photos, charts, arithmetic, etc to defend your position. An old phrase �baffle them with BS �comes to mind��

I think I will take some advice from Mr. Day and stop here. Trying to reason with you is pointless.

Please don�t e-mail me. I will not read it or respond. I�m finished here, but I look forward to FF�s review. |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-15-2007 10:50 PM

posted 08-15-2007 10:50 PM

quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

When requesting an independent, open-minded review, one generally does not then insist on what 'has' to be included...

I have not asked for any review, open-minded or otherwise, by anyone, including French. This thread also shows that Tim Furniss specifically solicited review(s) by FFrench. My earlier challenge was necessitated by French's posts, insisting on muddling my name and my work with those of Furniss. I really don't need, nor want, a review. The primary purpose of my posts here has been to inform a group of people I felt comfortable with, including, the humorous ones, about my Challenger work and some events that surrounded it before 1992. And the major points of my work were published in one place or another before 1992. Looking for a review of "my work" in 2007 makes me look like an idiot, and Tim doesn't seem to realize that. quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

Instead, you wait for the review

This (FFrench August 15 post) is granted. But, I would point out that it was French who violated this scholarly principle when he posted the day before (August 14): quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

I've learned a great deal about Furniss and AbuTaha and their work here as well as how their very different personalities interact with their work. And should someone pick up the Springer-Praxis book or one of the articles by Furniss and / or about AbuTaha in an old magazine article...

If French has already made up his mind, why continue? I posted here that the Praxis book (and others) was a revelation I found out about here. Based on the snippets quoted by Robert from the "Logs," I no less than described that presentation of my work rubbish, and a lousy infringement of my copyright. But French insists on referring again to my work in SP. As to the old magazine article French mentions, I consider that a "space tabloid" Oh yes, even I was tricked by the devious tactics of a tabloid reporter.It is "wearing," French. Your review should be about Furniss' work. On the Challenger chapter, perhaps, how Tim reported my work. But the validity, or lack of it, of the dynamic overshoot concept, lift-off loads, loads in struts, joint design, and the like should not be expected from you by anyone. This is not the place to resolve these issues, though I have no problem presenting my position and its opposite for everyone to read about. I have not read Tim's book, and I have no comments on how you handle that review. |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-16-2007 09:14 AM

posted 08-16-2007 09:14 AM

Some may misinterpret my reference to a "tabloid reporter" in my last post. I would never call Tim Furniss that. I thought FFrench would know who it was from his previous posts. quote:

Originally posted by FFrench:

That sounds familiar — if anyone has back issues of the UK magazine "Space Flight News" (no longer in existence) I seem to remember them covering his (AbuTaha's) theories in some detail.

That Space Flight News reporter first introduced himself as someone referred to me by a mutual friend, a respected space executive, and that he wanted to independently evaluate my Challenger work. I sent him a package of my work expecting private follow-up. The next thing I knew was this incredible "tabloid-like" spread in something called Space Flight News. Tim knows the identity of that reporter. Anyway, months later, I discovered from my friend that he had never heard of the reporter by name, publication or any other reputation. Talk about damage control. I am still recovering from that appalling incident 20 years later. You didn't read about "theories" of mine in that magazine, FFrench, that was, and remains, a tabloid account.

Ali AbuTaha |

GoesTo11

Member Posts: 1025

From: Denver, CO USA

Registered: Jun 2004

|

posted 08-16-2007 03:52 PM

posted 08-16-2007 03:52 PM

Is it possible for anyone to explain to a non-engineer in, say 500 words or less, exactly what the h*ll this thread is about?Just asking. Kevin |

FFrench

Member Posts: 3093

From: San Diego

Registered: Feb 2002

|

posted 08-16-2007 11:29 PM

posted 08-16-2007 11:29 PM

Review of �A Life In Space� by Tim Furniss.As someone who, like the author of this work, grew up in England, went through the grammar school educational system, had a childhood fascination with the space program and ended up drawn into a career closely tied with the space program, I may well be one of the more sympathetic reviewers that this work is likely to find. Growing up a generation later than Furniss, his more publicly-known work was one of the things that sparked and retained my own space enthusiasm, so I suspect I�m probably also therefore the kind of reader who this work is aimed at. As such, one way or the other, I knew that this would personally be an interesting work for me to read. And given the many questions that this work by Furniss has raised, it seemed like a comprehensive review was needed if the reader is to understand this work and be able to make an informed decision about whether to purchase it. Rather than a straight �space book,� the piece is most definitely biographical in nature, and the intent appears to be to chronicle Furniss�s entire life, whether the focus at that time was space or not. While an interest in space is a backdrop to his life story, the focus is always on Furniss himself and his personal life, and this is fact occupies far more of the writing than space stories. As such, it is impossible to create an entirely space-coverage-based review about this work, as the two are completely intertwined. It�s also important to note, additionally, that this work is not trying to give technical answers to controversial theories. A memoir, by its nature, is more based on events and opinions than technical debate. At times, the work appears to be an attempt to create something similar to British space journalist Reg Turnill�s book �The Moonlandings: An Eyewitness Account.� Yet this work is however quite different � not only in that it is an unillustrated Word document rather than a published book, but also in its content, as I will explain. The style of this work is interesting: written more like a series of loose journalistic notes rather than crafted into the smoother, more flowing style that one normally associates with a book. The sole advantage of this, perhaps, is that you do get a sense of immediacy, a feeling that the author is talking to you directly, as if he had just written an E-mail to you. The downside is that the piece feels continually fragmented, as if this were a set of notes for a book rather than an actual book, or a piece written solely for relatives to capture some family anecdotes. For example, one paragraph may be about being at the Kennedy Space Center � the next paragraph, Furniss is back in England driving a vehicle for the family business, with no transition given between the two experiences or places. Furniss also has a curious stylistic method of throwing what I assume are the newspaper headlines of the day into the middle of pieces of his text. This is presumably to help the reader understand the mood of the time he is discussing. At first, however, these headlines, added into the text without any explanation given of what they are, are rather puzzling and require repeated reading of a sentence to understand what Furniss is trying to convey. Sometimes they can never be quite understood, such as the phrase �Itsnotfair, Mummy,� thrown in quotation marks with no explanation into the middle of a paragraph about commercial space launches. This feeling of looseness is added to by a numerous sprinkling of spelling, grammar and punctuation errors: there are frequently a couple of errors to a page. Some of them are quite endearing in their underchecked charm, such as �Apollo moo landing.� Others, such as misspellings of movie and television show names, seem like the kind of fact that could easily have been checked and corrected. Most, such as �during the a talk show,� convey a sense that the author never re-read his own work after typing it. The language of this work is aimed not only very much at British readers, but is also written in such a way that non-Britons may have some difficulty understanding parts of it. References are made to terms such as Carry On films, the RAC, the Palladium and people such as Bruce Forsyth and Cliff Richard without any context given, which will puzzle those not deeply versed in British culture. Elsewhere, references to the AA without context may also confuse international readers used to this name in reference to alcoholics, not British car breakdown services. The language the work is written in will certainly confuse the non-Briton, with frequent use of phrases such as taking the mick, giving him stick, breaking his duck, bent coppers, knocked for six, drawing rooms, junket, prefects, pinnies, dormobiles, pud, rounders and crickers, snogs, jumpers, donkey jackets, happy bunny, grand lass, twee curtains, telly, loos, complete arse, knackered, a doddle, the Beeb, load of tosh, surnames, bit OTT, dodgy and little bleeder. Much of it may seem like a foreign language to many, even some Britons of later generations. Some phrases, such as �what a wooosie� and �it all ended in 10s,� are ones I have never heard myself despite living in the UK for two and a half decades. Other English phrasings, such as �Shepard had weed in his pants,� �absolutely gutted,� and references to �my mate Wang� and �fags� may give the American reader some momentary confusion as they adjust to quite different uses of common words. The work begins with a family history going back to Elizabethan times, followed by early childhood memories such as recollections of his grandparents and the delivery of the family�s first washing machine, and his favorite childhood television shows. Furniss seems to wish to evoke pathos and pity towards his earlier life, and describes himself in exhaustive detail as a �timid, weedy �. shy, wimpish �. insecure� boy who wet the bed, was regularly disturbed by nightmares about lions, and took refuge in his imagination by pretending to be a priest. This is emphasized with long descriptions of his formative years, with much information about physical punishment from strict teachers, regular bullying at school, and a wish thus to remain safely at home with his laboriously-made space scrapbooks. As the chapters progress, the bullying progresses to the attentions and demands of a number of pedophiles, and sexual abuse from older boys at his school, which make for disturbing reading. As well as space scrapbooks, amateur dramatic groups appear to have been another of Furniss�s escapes, and we are given many descriptions of the plays he appeared in and the reviews he received, including the costumes, such as see-through n�glig�es, that he wore. He describes much of his life as �all sorts of personal difficulties and dramas,� and that is certainly the impression that the long descriptions of them in this work would suggest. His relationships to women are self-admittedly strained, with explanations such as �trouble is, when they have a bit of bother and start crying, they blame everybody else and complain.� As he enters his teen years, we are given repeated descriptions of Furniss�s furtive fumblings with young girls in movie theaters, and his continued sexual frustrations over his failed attempts to lose his virginity, accompanying descriptions of girlfriends such as a �buxom Greek wench� and �she was completely frigid.� Much time and detail is given to musings that Furniss lived at home with his parents until the late age of 25, that when he moved out he was still a virgin, and that on moving out he remained �a loner, locking myself up in the house far too often.� He eventually sells his house and moves back home with his parents: he does not move out of his home town until the age of 40. Religion plays a role in the writing from its earliest chapters, and Furniss meticulously chronicles his childhood religious experiences, including a childhood experience of God apparently talking to him, �divine intervention� saving him from a car accident, and God�s spoken instructions to him later in life about house purchases. Furniss�s religious beliefs also color his space reporting, and he remains upset when stating that in his last hours Grissom apparently �blasphemed,� shouting � �Jesus Christ� � not in praise.� In my opinion, whatever one�s religious beliefs, this seems to be an odd criticism of a man about to face a horrific death. His uncontexted religious opinions also pepper other parts of the writings, such as a sudden reference out of the blue that �God ordained it to be� that the Apollo 8 crew read from the book of Genesis. These religious comments tie in to other thoughts given very early in the piece, querying commonly-accepted scientific theories, such as a sudden mention during the chronicling of his childhood that the Big Bang theory �defies belief� � not just in his opinion, but unequivocally. The 1976 Viking Mars missions are described less in terms of their mission objectives and more as a defense of creationism, which Furniss is evidently a strong proponent of to the point that no other viewpoint is apparently credible to him. The Viking coverage quickly becomes a lecture about the �unproven theory of evolution� and annoyance that creationism gets little coverage by a �subjective media.� When talking of the possibility of life elsewhere in the solar system and the universe, Furniss evidently believes that pondering the very possibility is �a way of denying a creator God,� and the idea is thus dismissed out of hand. Furniss�s political beliefs, never explained, are also interjected into the chapters with no context. Tony Blair is first referred to, with no explanation, as �Blairkovksy,� This theme appears in unexpected places later in the writing, with references to �President Blair� and Britain apparently living under �a dictatorship � like George Orwell�s 1984.� The UK under Blair is evidently �a morass of immorality, Godless laws and ultimately chaos.� These thoughts never seem to find connection with any other themes of the chapters. Intertwined in the midst of such reminiscences and opinions (and it is not possible to separate them from the personal context, as that is how the chapters are all written) there is the story of how Furniss grew interested in the space program � first as a plane-spotter, and then following Gagarin and Glenn�s flights, keeping books of clippings about their exploits. His interest is put into the context of a shy, bullied and abused young man looking for some kind of comfort and solace in the one area he knew more about than his contemporaries and adults. He describes talking to the photos of astronauts he has on his wall when he was a teen, and going back upstairs to say goodbye to them before leaving the house each day. His greatest moments of fleeting pride as a child seem to come when correcting adults talking about the space program. Furniss repeatedly also describes a �sexual analogy to a lift-off,� a theme which repeats when discussing spacecraft dockings and other space events, such as when he describes having sex as �performing dockings.� This interest eventually develops into work writing small articles for a space magazine, and how and why he was fired from that job, followed by detailed and lengthy descriptions of intermediate jobs such as working as a dishwasher, as a driver for a parcel company, and descriptions of the first furniture he ever bought for himself. No aspect of his life, however small, is overlooked. Furniss�s interaction with the space program has until now been almost entirely second-hand, mostly collecting clippings from his parents� newspapers, until a decision to fly to the US and observe the Apollo 13 launch. The most interesting and charming part of the writing to that point comes in his wide-eyed astonishment of a na�ve young man finally reaching the epicenter of his childhood imaginings. The section reads more as a personal list of where he went and who he talked to rather than a description for others (with details such as what he ate and which hotels had a television). But nevertheless his excitement at meeting astronauts who he still had photos of on his bedroom wall at home and how his �bedroom pictures came to life� is quite endearing. His eager description of the Apollo 13 launch is the first time in the writing that the reader really feels in the moment with Furniss. After more descriptions of his life outside of space work, we are given descriptions of how he began to write children�s space books, and, using the press pass of a rubber company he worked for at the time, attended the Apollo 15 launch. Seeing a second launch gives us a very similar description to his experiences watching Apollo 13, other than the addition of a description of the guilt he felt that he did not remember to thank God at the time for allowing him to meet astronauts. Furniss�s space career really starts to take off in 1981 as space interest in the UK picks up with the space shuttle, even more so when he is made redundant from a job in 1982 and begins to do more UK radio shows. In the meantime, we are also given more descriptions of his work in an industrial gas company, the office politics (�stabbed in the back� by colleagues), dressing up in drag for office parties, his depression and drinking problems, and hospitalization for nosebleeds. Regarded by colleagues as �a bit of a loner and peculiar, locking myself in my hotel room,� his stress manifests itself in stomach ulcers, and Furniss eventually admits �I wasn�t all that well mentally� and was on medication for depression. It is with somewhat of a sense of relief to this reader that Furniss�s life seems to stabilize somewhat when he marries, although the relationship begins as an affair with his then-married secretary, and we are given details of his lustful thoughts towards teenage foreign exchange students who live with the couple. As we learn more of his work as a reporter of the shuttle era, we receive more detail on the shuttles than we do on prior missions. Occasionally, mentions are made of forthcoming events in the writing, such as that he believes he was �partly instrumental in the sacking of Truly as NASA Administrator.� His STS-1 and 2 coverage begins the mentions in the writing of �dynamic overshoot pressure pulse,� a �dangerous oversight� that �NASA apparently disregarded or misunderstood.� These words are statements, never with explanations, presumably as it would not fit the loose style to veer into technical explanations. The personal life continues to be closely tied to the space coverage, and we are told about �a very insecure and sensitive soul� of a man who has chronic diarrhea attacks due to nerves before his television appearances. Furniss also admits to feeling �jealous� and �threatened� by other UK space reporters. A brighter point in the writing is his description of an invitation to tour Star City as a journalist, something he considers the real start of his space journalist career. Although less than three pages long, it�s an interesting insight, and we finally feel like we are getting some personal views into space reporting, the only prior example being the Apollo 13 coverage. As Furniss explains, the experience seemed to finally lead to his dream job � covering space stories for Flight magazine (spelled by Furniss as �Flight Intrenational�). Back at the Cape for the launch of STS 51-D, we are once again reading first-hand stories of space reporting at the scene, and the story picks up. But upon launch (described again in sexual terms as a �premature ejaculation,�) we learn that this is the only shuttle launch that Furniss ever witnessed. Amongst all of the numerous spelling errors in the writing, it is hard to know whether all the mistakes in the space coverage are unintentional errors or simply underchecked. Some non-English names, such as Furniss�s unorthodox spellings of �Nikolyev,� �Serefanov,� �Volnyov,� �Dzanibekov,� �Dumitri� Prunariu, �Rodolpho� Neri Vela, �Rushkavishnikov / Ruckavishnikov (depending on the chapter), � and even �Kruschev� may simply be his personal translations of Russian words, although there are far more commonly-used versions. Other misspelled names, such as �Wherner� von Braun, X-15 pilot Milt �Thomson,� astronauts �Elliott� See, Bob �Cripppen,� �Dale� Hilmers, �Frank Viebock,� Tom �Hennan,� Scott �Parazinski,� �Kiochi� Wakata, Payload Specialist candidate Chris �Homes� and space monkey �Bonny� (instead of the correct �Bonnie�) cannot have such a simple explanation. This also applies to technical equipment such as �Hasselbald� cameras, other space reporters such as Craig �Couvault� and Nigel �McKnight,� and television presenters he worked with such as Sarah �Green.� Trying to give the benefit of the doubt further, some space errors in the writing may simply be bad choices of words. When presumably trying to give an analogy for the VAB being taller than St. Paul�s Cathedral, Furniss states that the VAB is �big enough to accommodate St. Paul�s Cathedral.� The cathedral is, in fact, many feet wider than the VAB, so this would be impossible. Furniss�s description of heading �eastwards� from Edwards Air Force Base to San Diego during his first travels around the USA is confusing. Furniss refers to �Apollo 13�s commander Tom Hanks� while talking about the real flight, and the reader is left to assume that he suddenly decided to add a sentence about the movie too. Tranquility Base is misspelled. The Apollo CSM for ASTP is continually referred to as �Apollo 18,� despite it not officially being called by that assignation. It�s stated that Deke Slayton was still off flight status all through the Skylab program (1973-74) when in fact he was restored to flight status in spring 1972. Facts and quotations are given with misplaced conviction, such as the telegram sent to the Apollo 8 crew stating, in part, �You saved 1968� being instead described as a mailed letter stating �Thank you for saving 1968.� Ken Mattingly is described as retrieving �instruments� during his Apollo 16 EVA, rather than camera film. The Perseid meteor shower is renamed �the Perseus meteor shower.� The orange soil found on Apollo 17 is explained as �discoloured dust� rather than, more accurately, bead-like microscopic glass particles. These seem like small points, but they accumulate throughout the chapters and will probably create a mounting sense of doubt in the knowledgeable space reader. Other, larger air and space errors cannot be passed off as possible spelling errors or bad phrasing, and examples abound throughout the chapters. The tall, lean Ed White is described instead as �burly.� Frank Borman is described as the �first case of space adaptation syndrome,� which seems to overlook Gherman Titov and others who flew earlier. The name of the Apollo 10 Command Module is given as �Gumdrop,� which was of course instead the name for Apollo 9�s Command Module. STS 3 landed at White Sands because the Edwards runway was too wet, and yet in this work the reason given is �a sandstorm.� STS 41D is described as taking place in 1964. Albert 1 is described as �the first animal in space� on �a suborbital flight,� when in fact the flight only reached 37 miles and there is strong evidence that the animal had already perished while on the launch pad. John Cunningham is known as a test pilot for the Comet, not the Concorde. Charlie Bassett is described as set to join the crew of Apollo 12 had he not died � Furniss is confusing him with C. C . Williams. Technical terms seem to get confused or misunderstood frequently also, such as �30 rpm per second� and �intertial navigation.� Apollo 8 is described as the first �interplanetary flight� (the moon, of course, is not a planet). The Apollo 15 covers incident is, incorrectly, described as �the crew sold stamps they took to the moon and franked there.� Furniss also states that �potassium-laced orange juice� on the Apollo 15 mission helped cause Jim Irwin�s heart difficulties, when in fact a lack of potassium was probably part of the problem. Other coverage seems to use phrases abandoned in the 1950s or earlier, such as references to Guion Bluford as the �first negro astronaut� and �first coloured astronaut,� and similar references made to Mae Jemison. A French Presidential delegation is referred to as �The Frogs.� It is surprising to read this in a supposedly contemporary work. If I were Furniss, I would have also avoided writing about buying Chinese food from �chinkys.� Eventually, we come to his chapter about the Challenger disaster. Furniss clearly states that this is not intended to be a comprehensive investigation of what happened, more a description of what he reported and investigated at the time, which he eventually summarizes as �a monumental cover up.� Confidence in his work is not raised when the crews� names are misspelled as �Christa McCauliffe� and �Ellison Onuzuka.� Nevertheless, Furniss asserts that the first time he saw the launch footage the day of the tragedy, he could immediately tell the SRBs and SSMEs were behaving erratically. The O-ring issue is immediately described as a �red herring� based on this initial analysis, and the chapter describes his belief that the Rogers Commission missed evidence, the reason being, in Furniss�s opinion, the need to have the shuttle flying quickly again as a sign to the Soviets during the Cold War. According to Furniss the SRB was disintegrating from the beginning of the flight, which he says he personally witnessed on the British TV footage that day. The true cause of the accident, Furniss believes, is AbuTaha�s �dynamic overshoot� theory (although, despite such championing of his theories, Furniss always miscapitalizes his name as �Abutaha�). As such, Furniss in this chapter repeats many of AbuTaha�s theories, in a condensed, readable form, but such is the memoir nature of this work that they are not given in a way that supporting evidence is provided. For those looking for new evidence of why the shuttle may have been lost, it is not here: this is simply a memoir summarizing what Furniss believes. Furniss�s original work here, instead, is to go further than AbuTaha in his discussion of the politics surrounding the events: to try and support the theories by looking for political and office-politics events surrounding the disaster. Much of it sounds very like the office politics and firings that Furniss has described about his own earlier career. To accept Furniss�s version of events, the reader would have to believe (and, again, no detailed evidence is provided as this is a memoir), that: -There were behind-the-scenes conversations between NASA and Morton Thiokol to correct the true, hushed-up reason the SRB failed. -Other journalists and �people higher up� lost their jobs or were �posted to the colonies� for �digging too deep� into AbuTaha�s theories and asking too many questions about the shuttle disaster. -There was a general NASA cover-up of the truth (which Furniss poses as an open question and frequently alludes to) and a comparison is made to Watergate. -NASA censored images of the launch, �seizing� images from photographers and only publicly releasing images from carefully pre-selected angles or moments in the launch, and misled the Rogers commission with these selected images, which he equates to the JFK assassination �Zapruda� (sic) film. -A probable TIME magazine cover story showing �smoking gun� images was abandoned, as journalists were too scared of the aerospace community giant corporations. -Dick Truly ended up �falling from grace� as NASA Administrator due to the Challenger investigation aspects. -The Hubble Space Telescope mirror was not ground to the wrong specifications, but instead shifted out of place due to �dynamic overshoot� on launch. -Unnamed NASA officials somehow �paid later� for dismissing AbuTaha�s theories. -Scobee and Smith were aware of the shuttle �fishtailing� through the sky on ascent, but never mentioned this to the ground (unless you accept a complete revision of what their standard reports to the ground really meant). -NASA, while rejecting AbuTaha�s theories, covertly stole them and later reported them as their own. As Furniss continues the chapter and continues to summarize AbuTaha�s theories, his excitement level increases, and more and more sentences end in an exclamation point or a question mark as he grows ever more certain that, in summarizing AbuTaha, he knows the true, full story. As he describes how AbuTaha was isolated and ridiculed by his peers, his indignation grows, and the reader cannot help but consider the very similar descriptions of his own former relationships with colleagues that Furniss describes throughout his own career. An assumption can be made that Furniss identifies closely with AbuTaha as a misunderstood outsider who has been dismissed by those above him in a hierarchy. In championing AbuTaha, Furniss seems somehow to be striving for his own personal redemption. In an indication that the writing is constantly being updated, Furniss even references this very CollectSpace thread, stating that he was �insulted and slandered� here by those �who should have known better.� In his summary of events, Furniss also describes a scenario where he believes the crew could �bale out� of the orbiter had the shuttle survived until SRB separation. This suggests that Furniss believes the Challenger crew had parachutes and could have exited the vehicle using them. I shall leave it to the readers of this review to decide what that means about Furniss�s grasp of the Challenger shuttle, the accident and the crew�s survival options. We�re less than halfway through the writing at this point. Pleasingly, following such an emotionally charged chapter, the piece then settles, for a short while, into a far more fluid and sedate description of the next few years in space exploration, and the jobs Furniss had while covering it. Thankfully, the spelling and factual errors begin to abate and what follows is a far more readable summary of British space politics of the late 1980s onwards. It�s clear that Furniss feels on more confident ground here, presumably as he was far more in the midst of reporting the events of this time. For readers looking for Thatcher-era British space politics, this part of the writing may be of interest, although there are still odd interludes (such as Furniss�s description of watching porn on a hotel TV while at a space conference). We also have a readable account of a visit to Baikonur�s launch facilities, and a sense of the sparse desolation of the area. We also learn about Furniss�s fear of heights, such as a time he had a panic attack on a launch gantry and had to be helped down. Additionally, we learn of Furniss�s growing religious faith, with Jesus appearing to him in dreams, and this is intertwined with his space coverage, such as comments about the �arrogant certainties� of Big Bang theorists and the impossibility of life on Mars for religious reasons. Science correspondents, he states, �would be shot� if they endorsed creationism (by whom, we are not told). He states that his wife initially believed he had been �brainwashed� by religion. His championing of AbuTaha�s theories follows a similar pattern throughout the rest of the writing. When stating how the Hubble mirror was probably damaged by �dynamic overshoot,� he writes that �this could very well have been a cover up.� Similar statements (without supporting evidence, this being a memoir) are made for the Galileo dish deployment problems, and STS 40 cracked temperature sensors. He describes upsetting NASA officials and astronauts by asking them about AbuTaha�s theories, and that it was �clear� to him that NASA, Rockwell and the AIAA stole AbuTaha�s ideas without compensation or public acknowledgement. He states that the US media was �too scared� or �told by the government not to touch� the story. According to Furniss, President Bush senior was shown AbuTaha�s theories, and this led to NASA Administrator Truly being sacked. He believes that Administrator Goldin also sacked Bryan O�Connor as a direct result of his own Challenger magazine articles. No evidence is given, this being a memoir, but statements are made such as AbuTaha was �regarded as a danger by NASA.� We are told of his �secret meetings� (kept secret from whom, it is not clear) with AbuTaha, his belief that he was followed, his hotel room was switched and probably bugged, and that they were followed into restaurants. In this section, Challenger is described as �a convenient coverup.� The most fascinating, unexplained, paradoxical statement to me of this section is Furniss�s statement that his reporting work on dynamic overshoot was �received with absolute silence, a classic indication that it was right on the money.� At this point, there are 100 pages and ten years left to cover in the piece. I believe I have probably gained all I need to know of the author�s beliefs, style and tone of the writing, and reading the final third will add little to my understanding of the work. I hope that this review gives the general space reader a good overview and sufficient information to decide if this work is worth purchasing. |

aurora

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-17-2007 01:39 AM

posted 08-17-2007 01:39 AM

Great stuff French, I enjoyed it although the tone of the review was expected - a knocking job about my personal life with many events taken out of context to try to make me out as a nutcase, particularly my Christian faith. You don't convey the sense of my enthusiasm for space as a boy and a determination to become a space journalist which is the core of the early parts of the book. You glossed over the running "space history" element. I am sure readers will like to know much more for themselves. Thank you for pointing out the errors. The final version has of course all been spell-checked etc. I was really hoping you would enlighten the readers more about the Time Life images in particular. I believe that readers will really enjoy this autobiography and running space history - of which Challenger represents 10%. Also, you didn't finish the review. |

Naraht

Member Posts: 232

From: Oxford, UK

Registered: Mar 2006

|

posted 08-17-2007 03:18 AM

posted 08-17-2007 03:18 AM

Thank you, FFrench, for taking the time to write such a detailed review. It puts the author's story and the Challenger argument in context, and from my point of view offers more than enough information about the book. I know I'm not the only one who finds it a bit odd that for an author to demand that a reviewer address certain aspects of his book. |

mercsim

Member Posts: 138

From: Phoenix, AZ

Registered: Feb 2007

|

posted 08-17-2007 10:09 AM

posted 08-17-2007 10:09 AM

Wow! I think FFrench did a great job! I got the sense of "enthusiasm for space as a boy" and I believe FFrench conveyed this.The best thing I saw in all of the review was "...create a mounting sense of doubt..." Now that really fits this entire thread. Thank you FFrench. |

Ali AbuTaha

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-17-2007 10:19 AM

posted 08-17-2007 10:19 AM

quote:

Originally posted by Ali AbuTaha:

I am new to this thread, French, and I don't know "a great deal about" you. That's why I am eagerly awaiting your evaluations...

"Space" authors are lucky to have someone like "FFrench" review their works, and we are fortunate to benefit from his breadth and depth of knowledge in the field and his excellence of presentation.Ali AbuTaha |

ColinBurgess

Member Posts: 1567

From: Sydney, Australia

Registered: Sep 2003

|

posted 08-17-2007 10:30 AM

posted 08-17-2007 10:30 AM

Although I've been a mildly interested observer to the beginning and flow of this thread, I haven't been moved to this point to make any comment. However I couldn't help but notice Tim's response to the review in which he thanks Francis for pointing out those many factual and spelling errors - especially the names of people - and tersely states that he has now "of course" spell-checked the final draft. Why was this not done before now? Was it not the final draft that (according to your own statements) was previously being sold by you? And of course how does any spell check eliminate all those misspelt names of well-known identities offered in the review?Tim, with the greatest of respect for all your previous and highly commendable publications on spaceflight history over many years, your grudgingly tacit disapproval of the review you requested is a somewhat classic case of horses bolting after the closing of gates. Colin |

space1

Member Posts: 506

From: Danville, Ohio, USA

Registered: Dec 2002

|

posted 08-17-2007 11:34 AM

posted 08-17-2007 11:34 AM

Thank you, FFrench, for taking so much time to write such an insightful review as a service to all cS readers.------------------

John Fongheiser

President

Historic Space Systems, http://www.space1.com |

Dwayne Day

Member Posts: 532

From:

Registered: Feb 2004

|

posted 08-17-2007 12:32 PM

posted 08-17-2007 12:32 PM

quote:

Originally posted by mercsim:

The best thing I saw in all of the review was

"...create a mounting sense of doubt..."

My favorite part: "buxom Greek wench" |

bruce

Member Posts: 830

From: Fort Mill, SC, USA

Registered: Aug 2000

|

posted 08-17-2007 12:37 PM

posted 08-17-2007 12:37 PM

I enjoyed the review. I think it is amazingly fair and spot on. BTW, "spot on" is English for "very accurate". Which brings me to another point.Having lived in England for some time and been around British musicians for many years, I understand most of the colloquial phrases and some of the names referenced in Tim's writing. However, their use may confuse or turn off a non-Brit reader who might otherwise better understand and appreciate the text. Nicely done Francis! Best,

Bruce Moody |

Dwayne Day

Member Posts: 532

From:

Registered: Feb 2004

|

posted 08-17-2007 12:42 PM

posted 08-17-2007 12:42 PM

quote:

Originally posted by bruce:

Having lived in England for some time and been around British musicians for many years, I understand most of the colloquial phrases and some of the names referenced in Tim's writing. However, their use may confuse or turn off a non-Brit reader who might otherwise better understand and appreciate the text.

We Americans know what "buxom" means... |

Spoon

Member Posts: 69

From: Carlisle, England

Registered: May 2006

|

posted 08-17-2007 01:11 PM

posted 08-17-2007 01:11 PM

Dwayne,I'm no engineer, but I am aware of occasions when "buxom wenches" have been known to be the route cause of "dynamic overshoot"... Thank you for the review, FFrench, and the time you obviously invested in it on our behalf. I found it very enlightening. Ian |

Moonwalker1954

Member Posts: 236

From: Montreal, Canada

Registered: Jul 2004

|

posted 08-17-2007 02:13 PM

posted 08-17-2007 02:13 PM

Thank you Francis for this review. Now we can say "Amen" to this thread!Pierre-Yves |

aurora

New Member Posts:

From:

Registered:

|

posted 08-20-2007 08:09 AM

posted 08-20-2007 08:09 AM

The book "A LIfe in Space" is being removed from the website www.spaceport.co.uk and is therefore not for sale. | |

Contact Us | The Source for Space History & Artifacts

Copyright 1999-2012 collectSPACE.com All rights reserved.

Ultimate Bulletin Board 5.47a

|

|

|

advertisement advertisement

|

Topic Closed

Topic Closed