How 11 Deaf Men Helped Shape NASA's Human Spaceflight ProgramBefore NASA could send humans to space, the agency needed to better understand the effects of prolonged weightlessness on the human body. So, in the late 1950s, NASA and the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine established a joint research program to study these effects and recruited 11 deaf men aged 25-48 from Gallaudet College (now Gallaudet University).

Today, these men are known to history as the "Gallaudet Eleven," and their names are listed below:

- Harold Domich

- Robert Greenmun

- Barron Gulak

- Raymond Harper

- Jerald Jordan

- Harry Larson

- David Myers

- Donald Peterson

- Raymond Piper

- Alvin Steele

- John Zakutney

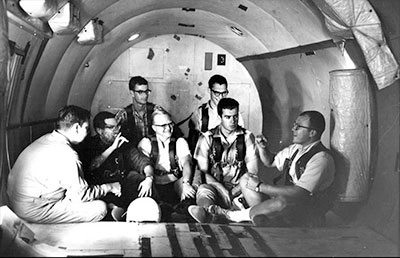

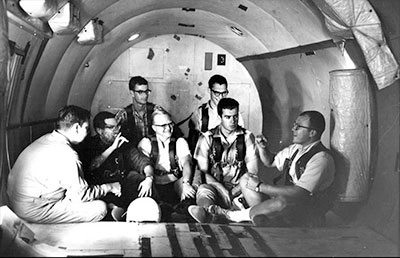

Above: Study participants chat in the zero-g aircraft that flew out of Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Fla. (U.S. Navy/Gallaudet University collection)

All but one had become deaf early in their lives due to spinal meningitis, which damaged the vestibular systems of their inner ear in a way that made them "immune" to motion sickness. Throughout a decade of various experiments, researchers measured the volunteers' non-reaction to motion sickness on both a physiological and psychological level, relying on the 11 men to report in detail their sensations and changes in perception. These experiments help to improve understanding of how the body's sensory systems work when the usual gravitational cues from the inner ear aren't available (as is the case of these young men and in spaceflight).

"We were different in a way they needed," said Harry Larson, one of the volunteer test subjects.

Above: Study participant John Zakutney is lowered into a centrifuge pod. (NASA/U.S. Navy/Personal collection of David Myers)

The experiments tested the subjects' balance and physiological adaptations in a diverse range of environments. One test saw four subjects spend 12 straight days inside a 20-foot slow rotation room, which remained in a constant motion of ten revolutions per minute. In another scenario, subjects participated in a series of zero-g flights in the notorious "Vomit Comet" aircraft to understand connections between body orientation and gravitational cues.

Another experiment, conducted in a ferry off the coast of Nova Scotia, tested the subjects' reactions to the choppy seas. While the test subjects played cards and enjoyed one another's company, the researchers themselves were so overcome with sea sickness that the experiment had to be canceled. The Gallaudet test subjects reported no adverse physical effects and, in fact, enjoyed the experience.

Test participant Barron Gulak later remarked about such experiments: "In retrospect, yes, it was scary... but at the same time we were young and adventurous."

Based on their findings from a decade's worth of experimentation, researchers gained insight into the body's sensory systems and their responses to foreign gravitational environments. Through their endurance and dedication, the work of the Gallaudet Eleven made substantial contributions to the understanding of motion sickness and adaptation to spaceflight.

Above: Exhibit ribbon-cutting ceremony at Gallaudet University Museum. From left to right: Gallaudet exhibit curator Margaret Kopp, NASA Chief Historian Bill Barry, Dr. Paul DiZio of the Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory at Brandeis University, Harry O. Larson ('61), Barron Gulak ('62), David O. Myers ('61) , Gallaudet University President Roberta J. Cordano, and Provost Carol J. Erting. (Jean Bergey, Gallaudet University)

On April 11, 2017, chief historian Bill Barry had the honor of representing NASA at the opening of Gallaudet University's museum exhibit Deaf Difference + Space Survival. Curated by Gallaudet student Maggie Kopp, the exhibit highlights the relatively unknown contributions to the study of motion sickness made by these 11 university alums for a decade from 1958 to 1968. Present were three of the 11 former study participants: Harry O. Larson, class of '61, Barron Gulak, class of '62, and David O. Myers, class of '61.