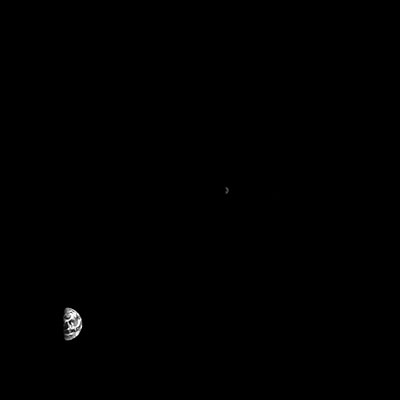

Planetary defense mission Hera heading for deflected asteroidESA's first planetary defense spacecraft has departed planet Earth. The Hera mission is headed to a unique target among the more than 1.3 million known asteroids in our Solar System – the only body to have had its orbit shifted by human action – to solve lingering mysteries associated with its deflection.

By sharpening scientific understanding of the 'kinetic impact' technique of asteroid deflection, Hera aims to make Earth safer. The mission is part of a broader ambition to turn terrestrial asteroid impacts into a fully avoidable class of natural disaster.

Developed as part of ESA's Space Safety programme and sharing technological heritage with the Agency's Rosetta comet hunter, Hera lifted off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, USA, on 7 October at 10:52 local time (16:52 CEST, 14:52 UTC) with its solar arrays deploying about one hour later.

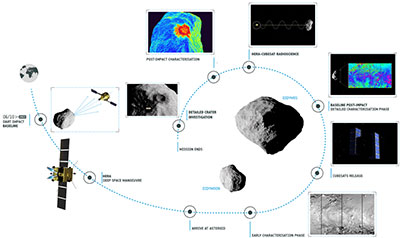

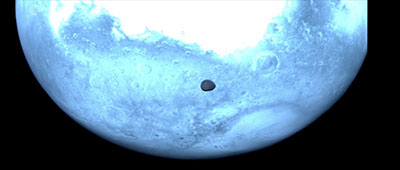

The automobile-sized Hera will carry out the first detailed survey of a 'binary' – or double-body – asteroid, 65803 Didymos, which is orbited by a smaller body, Dimorphos. Hera's main focus will be on the smaller of the two, whose orbit around the larger asteroid was changed by NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, demonstrating asteroid deflection by kinetic impact, in 2022.

"Planetary defense is an inherently international endeavour, and I am really happy to see ESA's Hera spacecraft at the forefront of Europe's efforts to help protect Earth. Hera is a bold step in scaling up ESA's engagement in planetary defense," said ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher.

Hera will also perform challenging deep-space technology experiments including the deployment of twin shoebox-sized 'CubeSats' to fly closer to the target asteroid, manoeuvring in ultra-low gravity to acquire additional scientific data before eventually landing. The main spacecraft will also attempt 'self-driving' navigation around the asteroids based on visual tracking.

The mission's launch and journey into deep space is being overseen from ESA's European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

"Hera is finally on its way to Didymos; today we are writing a new page of space history," said Hera mission manager Ian Carnelli. "This deep space mission took shape from contract signing to launch in only four years, a testimony to the hard work and dedication of the Hera team across ESA, European industry, science, and the Japanese space agency JAXA".

"But the underlying idea of a planetary defense mission based on one spacecraft impacting an asteroid with a second that gathers data goes back two decades, with a significant contribution made by the late Prof. Andrea Milani, a pioneer in asteroid risk monitoring whose name has been lent to one of Hera's two onboard CubeSats."

ESA, together with NASA and other partner agencies, maintains a watch on the sky to identify and track dangerous asteroids. But if an incoming body was spotted, what if anything could be done to stop it?

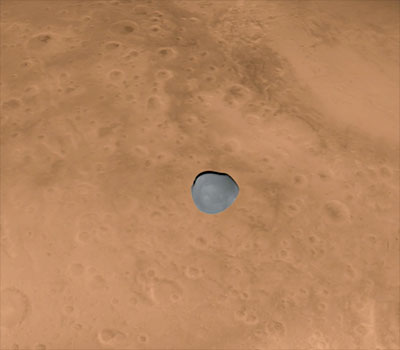

NASA's DART mission was created to help answer that question. On 26 September 2022, the DART spacecraft performed humankind's first asteroid deflection by intentionally crashing into Dimorphos, the Great-Pyramid-sized moonlet of the larger, mountain-sized asteroid Didymos, shifting its orbit.

Based on observations from Earth, DART succeeded in shrinking the orbit period of Dimorphos around Didymos by 33 minutes, nearly 5% of its original value, while also casting a plume of debris thousands of kilometres in space.

But many unknowns remain about the event, which scientists need to resolve in order to help turn this 'kinetic impact' method of asteroid deflection into a well understood and reliably repeatable planetary defense technique. How big was the crater left by DART's impact, or did the entire asteroid undergo reshaping? What is the mineralogy, structure and precise mass of Dimorphos?

With a cube-shaped main body measuring approximately 1.6 m across and flanked by twin 5-m solar wings, the Hera spacecraft is ESA's own contribution to this international planetary defense collaboration. Once it reaches the Didymos binary asteroid in two years' time, the mission will perform a close-up 'crash scene investigation' to gather all the missing knowledge needed.

"Hera's ability to closely study its asteroid target will be just what is needed for operational planetary defense," explains Richard Moissl, heading ESA's Planetary defense Office. "You can imagine a scenario where a reconnaissance mission is dispatched rapidly, to assess if any follow-up deflection action is needed. We should soon be practicing this again with our Ramses spacecraft, a proposed planetary defense mission to rendezvous with the Apophis asteroid during its close approach to Earth in 2029."

Around 100 European companies and institutes across 18 ESA Member States have been involved in developing the Hera mission. OHB System AG led the industrial consortium, including responsibility for the overall spacecraft design, development, assembly and testing.

Hera will perform the most detailed exploration yet of a binary asteroid system. Although binaries make up 15% of all known asteroids, none has ever been surveyed in detail. In addition, the Dimorphos asteroid is the smallest body yet visited by a space mission while Didymos is a fast spinner for its size, coming close to the limits of structural stability given its dimensions.

The Milani CubeSat, developed for ESA by Italian industry led by Tyvak International, will survey the mineral makeup of Dimorphos and its surrounding dust, while the Juventas CubeSat, produced by a Luxembourg-led consortium under GOMspace, will perform the first subsurface radar probe of an asteroid. Late in its six-month asteroid survey, Hera will also test out an experimental self-driving mode that will allow it to navigate around the asteroids autonomously based on monitoring of surface features.

ESA Hera mission scientist Michael Kueppers comments: "By the end of Hera's mission, the Didymos pair should become the best studied asteroids in history, helping to secure Earth from the threat of incoming asteroids."

Hera Principal Investigator Patrick Michel, Director of Research at CNRS / Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, adds: "DART's impact was like the first episode in a cosmic adventure – a spectacular flash seen across space that left scientists with the question: what happened next?"

"Now Hera is on its way in the next episode, to turn the brief glimpses of the Didymos asteroids that the DART mission beamed back to us into a detailed survey, promising us fresh insights into the planetary collision process – which has been one of the primary mechanisms for creating the Solar System as we know it."