NASA's Gemini IX mission was another step in developing technology for future spaceflights from Apollo to the agency's Journey to Mars. But this mission included developing alternate plans when faced with the unexpected.

Gemini IX provided NASA with crucial experience in learning how to be flexible, expanding skills in orbital rendezvous and gaining a better understanding of the challenges faced by spacewalking astronauts.

The three-day mission was designed to be similar to the previous flight in March 1966. After achieving the first orbital docking, Gemini VIII was brought home early due to a failed spacecraft thruster. The Gemini IX crew hoped to gain further experience in rendezvous, docking and working outside the capsule. Plans also called for performing a complex spacewalk using a self-contained rocket backpack, called the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit, or AMU.

The original Gemini IX command pilot was scheduled to be Elliot See, with Charles Bassett as pilot. They were both killed on Feb. 28, 1966, when their T-38 jet crashed into the McDonnell Aircraft plant in St. Louis, where assembly of their spacecraft was being completed.

The backup crew of Tom Stafford as command pilot and Eugene Cernan as pilot then were named for the upcoming flight. A veteran of Gemini VI the previous year, Stafford would go on to command Apollo 10 in 1969 and the Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975.

Cernan was lunar module pilot with Stafford on Apollo 10 and commanded the final moon landing mission, Apollo 17, in December 1972.

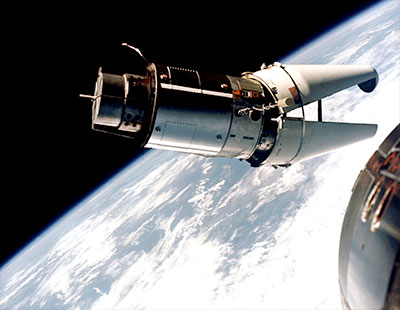

Above: An Augmented Target Docking Adapter, or ATDA, launches atop an Atlas rocket from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station's Launch Complex 14 on June 1, 1966. The ATDA served as a rendezvous target for Gemini IXA.

Gemini IX's Agena target vehicle was launched by an Atlas rocket on May 17, 1966. Stafford and Cernan were already aboard their spacecraft poised to lift off 90 minutes later as the Agena competed its first orbit. However, the Atlas malfunctioned in flight, and the Agena failed to reach orbit.

Launch of Gemini IX would have to wait.

Even so, Dr. George Mueller, NASA associate administrator for Manned Space Flight, had high praise for the launch team, noting that the simultaneous countdowns at Cape Kennedy Air Force Station's Launch Complexes 14, for the Atlas-Agena, and 19, for the Gemini-Titan, had been the "smoothest yet in the Gemini Program."

While the next Agena would not be available until summer, NASA had a backup rendezvous target available, called an Augmented Target Docking Adapter, or ATDA. Additionally, the mission was redesigned Gemini IXA.

"We had a flexible flight plan allowing us to shift around items and that's exactly what happened," said Stafford.

The contingency target vehicle was developed after an Agena failed to reach orbit for the original Gemini VI mission. This spacecraft would allow Gemini flights to continue without delaying the goal of landing on the moon before the end of the decade of the 1960s.

The ATDA was built by the McDonnell Corp., prime contractor for the Gemini spacecraft. The ATDA used a Gemini spacecraft re-entry control section and other already proven equipment. Like the Agena, it was launched atop an Atlas rocket on June 1, 1966, and successfully reached an orbit 161 miles above the Earth.

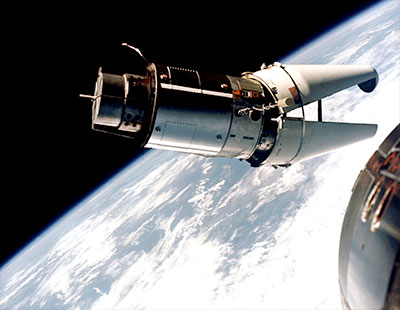

Above: The Augmented Target Docking Adapter, or ATDA, as seen from the Gemini IXA spacecraft during one of their three rendezvous in Earth orbit. Failure of the docking adapter protective cover to fully separate on the ATDA prevented the docking of the two spacecraft. As a result, command pilot Tom Stafford described the ATDA as looking like an "angry alligator."

However, telemetry soon indicated more unexpected news. The conical nosecone shroud at the top of the ATDA appeared not to have separated. If that was the case, docking would be impossible as the shroud covered the target vehicle's docking collar.

After a two-day delay, Stafford and Cernan were launched on June 3, and they would soon learn the condition of the shroud.

Stafford fired his thrusters 49 minutes after liftoff to begin closing in on the ATDA. Radar contact was achieved when the two space vehicles were 150 miles apart. Stafford and Cernan spotted the ATDA at three hours, 20 minutes into the mission, when they were 58 miles away.

As they closed in, Stafford began to describe what they saw.

"We've got the ATDA in reflected moonlight at about 3 1/2 miles," he said.

As they closed in at about 900 feet, Stafford reported his first good view of the ATDA.

"That's a weird looking machine," he said. "Would you believe that there's a nose cone on that rascal. The shroud is half open. It looks like an angry alligator out there rotating around."

The shroud was supposed to open in two halves and drop away during launch. It split in two, but was hung up at the base. While the rendezvous was successful, the alligator-like "jaws" would prevent docking unless there was a way to push it aside.

"You could almost knock it off," Cernan said.

Stafford suggested to spacecraft communicator Neil Armstrong in Mission Control Houston that they be allowed to extend a docking guide bar on the nose of the Gemini to gently bump the shroud in an attempt to knock it off.

Armstrong, who commanded the previous flight, relayed word that Flight Director Eugene Kranz vetoed the idea as too risky.

While the docking was ruled out, Stafford and Cernan gained valuable experience and data on different approaches to rendezvous, a maneuver that would be crucial as Apollo astronauts in a lunar module returned to the command module after exploring the moon.

Gemini IXA preformed a second rendezvous moving away from the ATDA and then successfully completed an approach from below. It also was the first pure optical rendezvous.

"Gene made all the computations and we did not use the computer," Stafford said. "We wanted to test how good man can visually judge distance."

This required learning how to best interpret visual cues.

"We had anticipated that silver paint (on the ATDA) actually would be almost equivalent to white in visual acquisition, but it certainly was not," Cernan said. "We could more easily see the white shroud in reflected moonlight."

At one point, the Gemini IXA crew used an onboard system to verify Stafford's estimation that they were about one mile from the ATDA.

"The radar said we were at 1.1 mile," he said. "It was obvious we could judge distance in close."

On flight day two, they approached the ATDA a third time, simulating a lunar module returning to the command module in lunar orbit. They learned that the rendezvous radar would be required for this approach.

Stafford then backed off from the target vehicle to prepare for the next day's ambitious spacewalk.

During America's first spacewalk a year earlier, Gemini IV astronaut Ed White floated around for 20 minutes. Cernan planned more than two hours of task evaluations and work testing the AMU. It was equipped with propulsion, a stabilization system, oxygen and telemetry for biomedical data.

Above: During his two hour, eight minute spacewalk on June 5, 1966, Gemini IXA pilot Eugene Cernan is seen outside the spacecraft. His experience during that time showed there was still much to be learned about working in microgravity.

As Cernan floated through the Gemini hatch, he described what it is like being outside.

"Boy, is it beautiful out there, Tom," he said, "and what a beautiful spacecraft."

After his experience on Gemini IV, White recommended handholds to assist future spacewalkers. For Gemini IXA, Cernan tested Velcro for that purpose.

"I started using one of those Velcro pads and I lost it," Cernan said. "It came right off my hand. The Velcro's not strong enough."

Cernan then worked his way back to the aft section where the AMU was located. Once he reached the AMU in the spacecraft's adapter section, Cernan realized his spacesuit provided limited maneuverability. He was unable to gain any leverage for his planned tasks due to the lack of hand and foot holds. It also was difficult to turn valves and perform simple movements.

The extra effort caused the heat to rise in Cernan's spacesuit, and his increased respiration resulted in his helmet visor beginning to fog up.

"He's fogging real bad," said Stafford to officials in Mission Control. "The AMU controller arms presented far more difficulty to us in zero g than they did in the simulation."

With Cernan barely able to see, Stafford and mission control agreed to bring him back in after two hours and eight minutes outside the spacecraft.

The next day, June 6, Stafford and Cernan fired Gemini's retro rockets on their 45th orbit of the Earth. They landed less than one mile from the prime recovery ship, the USS Wasp. It was the first time a spacecraft descending on its parachute was shown on live television.

Above: Gemini IXA splashes down in the Atlantic Ocean on June 6, 1966, less than one mile from the prime recovery ship, the aircraft carrier USS Wasp. It was the first time a spacecraft descending on its parachute was shown on live television.

The flight's lessons learned resulted in NASA mission planners adding even more flexibility into future flight plans. On Gemini IXA, Stafford and Cernan were able to work with flight controllers to demonstrate sophisticated rendezvous maneuvers were workable and applicable to Apollo and future space programs. Cernan's experiences on his spacewalk showed there still was much to be learned about working in microgravity outside a spacecraft.

"We came back with some data and recommendations on how to handle yourself when floating in close proximity to the spacecraft," Cernan said in the postflight news conference.

As a result of Cernan's experience, important changes were made for planning future work outside a spacecraft, including adjustments to the workloads for future Gemini spacewalks. For Apollo moonwalks, the spacesuits were designed differently.

A Gemini spacesuit was cooled by air flow. Apollo spacesuits for moonwalkers and for those astronauts who work outside today's International Space Station would be cooled by having the astronaut wear an undergarment with small tubes circulating water near the skin.