Space Cover #534: Apollo 13 Crew Proves the Meaning of LuckyCharlie Duke, in the backup crew for Apollo 13, had picked up a bad case of the German measles from his children and had subsequently exposed the backup crew and prime crew to the measles a week before the flight. Extensive blood tests indicated that everyone had protective immunity to the disease from having had it before, except Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly in the prime crew. Mattingly was in serious danger of contracting the disease ten days after his exposure to the measles and during Apollo 13's flight to the Moon.

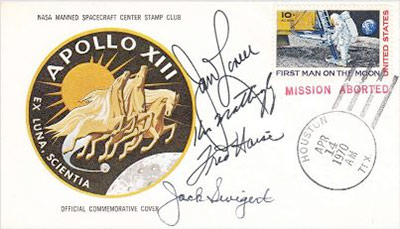

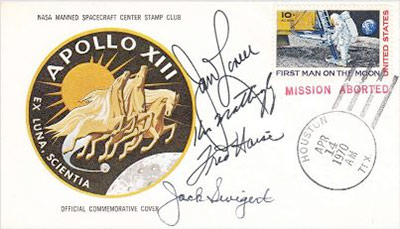

He is replaced as CM pilot in the prime crew by backup pilot Jack Swigert. NASA managers and the crew are not superstitious, but there is an unusual commonality for the flight. Designated as Apollo 13, liftoff is scheduled for 13:13 local time, and the spacecraft Odyssey will enter the Moon's gravity on April 13, 1970. Commander Jim Lovell scoffs at this, until Charlie Duke catches the German measles and exposes both the backup crew and the prime crew to them as well.

Marilyn Lovell had felt uneasy since the previous August when she learned that her husband Jim Lovell would command Apollo flight number 13. It wasn't that she was superstitious. Jim Lovell had been too lucky too long, and she felt it was only a matter of time until her husband's luck would run out. But, she also knew how much this flight as Commander of Apollo 13 meant to him. After eight years of training as an astronaut, her husband was finally going to command a mission to land on the Moon.

Prior to the launch of Apollo 13, Marilyn had traveled to Cape Canaveral to see Jim, and she had planned to return to their home in Houston to watch his launch. She stayed at the Cape instead to say goodbye the way she had on his Apollo 8 flight. Watching Apollo 13 rocket away from launch pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center on a bright white hot thundering plume, she quietly whispered, "Goodbye" and was thankful that everything was going well. She was also contemplating Jim's comment as they walked on the beach at the Cape a few days before, that Apollo 13 would be his last flight.

Jim Lovell had named the Command Module Odyssey because he liked the sound of it and noted that in the dictionary, odyssey was defined as a long voyage marked by many changes of fortune. For the lunar module, he chose Aquarius from Egyptian mythology, the water carrier who brought fertility and knowledge to mankind. Apollo 13 completes its countdown and launches with an explosive roar at 13:13 on April 11, 1970. Three hours later, Apollo 13 with Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert blasts-out of Earth's orbit heading to the Moon.

NASA officials recognized that the landing at Fra Mauro would be a very difficult landing to accomplish by the crew of Apollo 13. By comparison, the flights of Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 had touched down in landing at friendly plains locations on the lunar surface. Geologically speaking, though, the lunar hills and mountain ranges held more promise for answering the questions of whether or not the Moon was made of the same geological material as the Earth and if the Moon was of the same age. The higher Moon elevations even reflected sunlight differently from its lower elevations necessitating further analysis.

Apollo 13's proposed landing location was planned for the Moon's Fra Mauro mountain range, an aged Appalachian type weathered mountain range approximately 110 miles east of the Apollo 12 landing site. It was anticipated that Fra Mauro would yield better geological rock and soil samples to Apollo 13's Moon walkers and in turn to scientific teams on Earth involved in lunar research. The task of navigating Lunar Module Aquarius into the designated lunar landing site would also provide a critical test of a Lunar Module Pilot’s skill and ability to land under challenging conditions.

Landing on the Moon would be difficult enough, but the lunar landing site at Fra Mauro would indeed be a challenge. A free return trajectory approach which had worked so well on the two earlier Moon landing missions was changed for this flight. The rough terrain at Fra Mauro made the landing site a dangerous one. The ambient lighting for the projected landing time on the lunar surface was considered poor with normal shadows for the Moon’s topography at the wrong angle and not useable. Without shadows defining craters, obstacles, rocks, and rifts, a clear landing site would be much more difficult to determine by the crew descending to the lunar surface. The crew would have only one shot in making the lunar landing, and the landing would be perilous.

Jack Swigert checked his instruments and sees that there is a sudden and unexplained loss of power in main bus B, one of only two main power distribution panels providing power to all the hardware and systems in the Command Module. The bus losing power is a serious problem. Half of the hardware and systems in the spacecraft are dead.

Swigert immediately reports to Apollo Control, "We've got a problem here." CapCom Jack Lousma in Houston and puzzled, says, "This is Houston, say again, please?" Lovell intercedes and yells,"Houston, we've had a problem. We've had a main B bus undervolt!" EECOM Engineer George Bliss in Houston, jumps-in and says, "We've got more than a problem." Sy Libergot glances at his instruments and sees the data for the spacecraft's oxygen tanks. Oxygen tank number two holding half the oxygen for the Apollo 13 flight appeared to be empty.

Jim Lovell was frustrated, and exasperated. He decided to make a quick check around the spacecraft as if he were doing a preflight check to try to determine what in the world was happening. As he looked out of the spacecraft window, he sees a thin, gauzy looking white cloud surrounding Odyssey and the Service Module and forming an iridescent halo that extended from Apollo 13 far into the black distance. He immediately recognizes the serious danger the crew is in as their oxygen from their oxygen tanks appears to be venting. He reports to Lousma in Apollo Control, "We're venting something into space."

He quickly observes that oxygen tank 2 is empty and oxygen tank 1 is slowly dissipating into space. If true, there only would be enough oxygen left for five hours of stay time in Odyssey. Lovell does some quick calculations and realizes that from this point in their transit to the Moon, their return to Earth would take approximately 100 hours. He straight forwardly says to his crewmates, "If we're going to get home, we're going to have to use Aquarius." Jim Lovell's desperate plan is to use lunar module Aquarius as a "lifeboat" for the crew to return safely to Earth. Apollo 13's Moon landing was off.

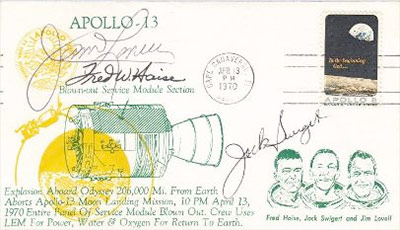

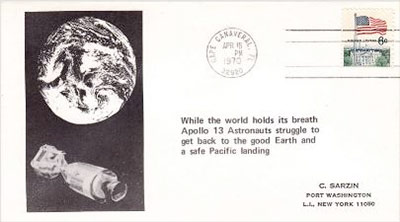

The cover above shows a graphic depiction of the blown-out section of the Apollo 13 service module that occurs after the oxygen tank explosion on Apollo 13 at 9:54 pm, April 13, 1970, in translunar insertion enroute to the Moon. The oxygen level reads zero in tank two and oxygen is spewing out of tank one at an alarming rate. The crew is told they have less than 40 minutes of oxygen left in Odyssey and are directed to power down non-critical systems on Odyssey and to evacuate to their lunar module Aquarius.

Jim Lovell after manning Aquarius reports, "Ok, Aquarius is powered up and Odyssey is completely powered down." Swigert takes a last look around in Odyssey as the last crew mate there. He leaves by weightlessly floating through the tunnel into the lunar module and rejoins his crew mates. He becomes a command module pilot with a dead spacecraft. He quietly comments, "It's up to you now."

The burn is precise and requires no smaller burn, called a trim. Aquarius speeds on its way around the Moon at an expected altitude of 136 miles off the lunar surface instead of the 60 miles that would have been used for executing its lunar landing. As Aquarius rounds the Moon, Lovell recalculates the earliest time the crew could reach Earth, but he is extremely concerned. He comes up one day short.

NASA officials in Apollo Control determine that a free return burn and loop around the moon will provide an accelerated return back to Earth. Lovell comments, "make sure we get this burn-off right." At the designated time, Lovell flips the master arm switch on. The LM computer flashed 99:40, a computer signal asking if the Commander was sure he wanted to make the burn. Lovell hits the proceed button and has ignition and low throttle. Jack Lousma in Control says, "Aquarius, you're looking good!"

The Pericynthion plus 2 burn, a speed-up burn, shortened as PC+2, would be a slower and longer burn after Apollo 13's Aquarius rounded the Moon. The speed-up burn would put the crew on a faster and revised computer derived trajectory back to Earth with a safer recovery window. Taking their improvised stations in Aquarius, Lovell reports, "We are go for the burn." As the countdown for the burn signals zero, the crew feels the LM's rocket engine slowly rumbles to life beneath their feet. The burn runs for two minutes and forty seconds.

As their speed-up burn is completed as relayed by CapCom, Lovell yells, "Shutdown," at the completion of the burn period. Capcom Vance Brand parlays, "Roger, shutdown. Good burn, Aquarius!" Houston Control in contact with the communications team on the designated primary recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima, relays voice message, "Pericynthion plus 2 burn complete. Predicted splashdown 600 miles southeast of American Samoa, at 142 hours, 54 minutes ground elapsed time."

NASA recovery team's Mel Richmond at sea on USS Iwo Jima turns to the ship's Communications Officer next to him and says, "It looks like we will have work to do this Friday." On Aquarius, though, Jim Lovell did not feel quite as confident. They were only 15,000 miles from the Moon and 225,000 miles from Earth. Aquarius mated with Odyssey still had a very long way to go.

Now 130,000 miles from Earth and rocketing back at 3,427 miles per hour, the spacecraft's return track again deteriorates into a shallow return with the possibility of it skipping off the Earth's atmosphere in an unsuccessful reentry. Control asks the crew to transfer LM power to the Command Module to recharge their reentry battery. Lovell asks if the procedure was tested, and CapCom Joe Kerwin haltingly responds "No." Swigert repeats Control's answer to Lovell and further states, "no, we can't get home without it."

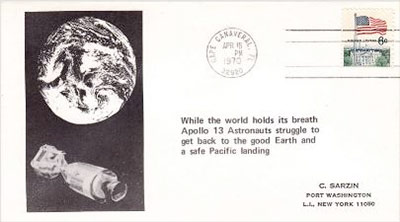

A final midcourse burn is made by the crew to improve the return flight path angle. Now, a prime news media and front page newspaper item, the reentry of Apollo 13 back to Earth holds the world's attention as it approaches Earth from 37,000 miles out and increased speeds up to 7,000 miles per hour, well inside Earth's gravity pull. The flight will splashdown in only six hours, but Apollo 13 must still jettison its inoperative service module, lifeboat and lunar module Aquarius, and has to successfully touchdown now as planned in the South Pacific.

Ship's Chaplain Philip Jerauld prays on USS Iwo Jima and gives thanks for the safe return of the Apollo 13 crew in a red carpet welcome on the ship's flight deck after the crew's heroic flight back and safe recovery in the South Pacific. As the crew did not land on the Moon, no quarantine period was necessary upon completion of their flight.

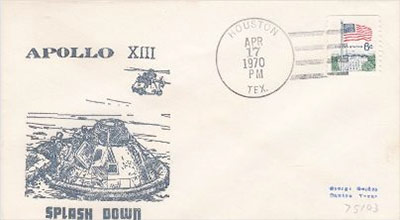

As Odyssey's three main parachutes follow the drogue chutes and unfurl, Jim Lovell tells his crew, "Hang on, if this is anything like Apollo 8, it could be rough." Thirty seconds later, Odyssey splashes down gently into the ocean and nothing like Apollo 8's hard jolting splashdown.

Buoyed up by the gentle Pacific Ocean, Lovell, Haise, and Swigert glance out their portholes. Jim Lovell says, "Fellows, we're home!"

The Apollo 13 crew by their bravery in the face of extreme adversity also proved the meaning of lucky for their safe recovery back on Earth despite incredible odds against them, after an aborted lunar mission, and their emergency return back to Earth.

— Steve Durst SU 4379