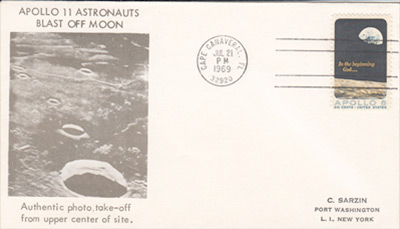

Space Cover #517: Apollo 11 goal achievedApollo 11's 110-meter-high Saturn V blasts away from LC-39.

The Saturn V's liftoff is spectacular with a bright white-hot trailing tail of consumed propellant blasting the huge rocket off launch pad A at LC-39, Cape Canaveral, Florida. It takes twelve seconds for Apollo 11's Saturn V to rocket clear of its tower. The impressive and powerful Saturn V rocket continues to accelerate and thunders into its trajectory and translunar injection for the Moon at a speed of 24,226 miles per hour. It is a spectacular and magnificent sight!

The Apollo 11 crew of Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin, Jr., and Michael Collins agreed not to achieve lunar orbit exhausted the way the Apollo 8 crew had done it. As they rocketed to the Moon, they contended their mission had not really started. It would not start until Armstrong and Aldrin entered lunar module Eagle, left Columbia, and began their powered descent to the lunar surface.

As they approached the Moon, though, the play-acting was getting harder and harder to maintain. In the crew's mind, landing on the Moon, safely returning to their spacecraft Columbia, and returning to Earth was at best only a fifty-fifty proposition.

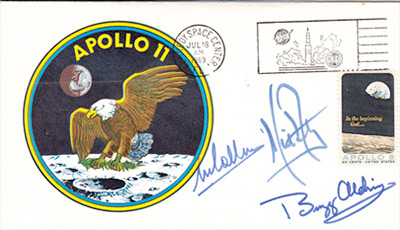

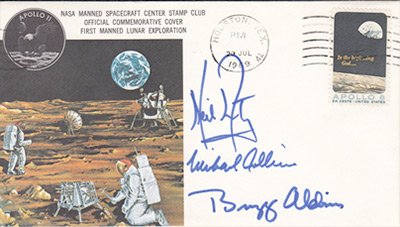

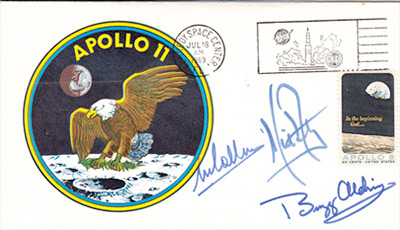

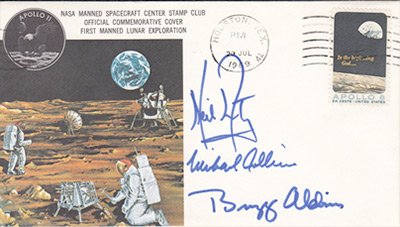

An Apollo 11 astronaut insurance cover is shown signed by Mike Collins, Neil Armstrong, and Buzz Aldrin, and is cancelled on the crew's launch date July 16, 1969, at Kennedy Space Center, Florida. The covers are held by the families of the astronauts until their safe return from their mission to the Moon and back to Earth. The Apollo 11 flight is the first space mission to have astronaut insurance covers.

It takes twelve seconds for Apollo 11's Saturn V to rocket clear of its tower. The impressive and powerful Saturn V rocket continues to accelerate and thunders into its trajectory and translunar injection for the Moon at a speed of 24,226 miles per hour. It is a spectacular and magnificent sight!

All three Apollo 11 crew members, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins, are already experienced astronauts. The acceleration of the Saturn V rocket feels normal to the crew and much like the acceleration they experienced with the Titan II rocket booster in the Gemini program. As Apollo 11 rockets to the Moon, it's track is extremely accurate and requires only one minor midcourse guidance correction of a three second burst from a service propulsion engine to change the spacecraft's velocity by six feet per second.

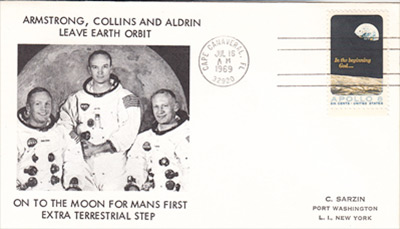

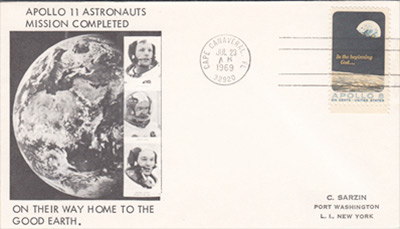

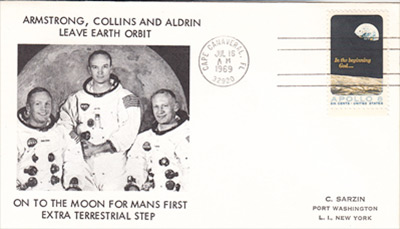

NASA's formal portrait of the Apollo 11 crew serves as the cachet for this Apollo 11 launch cover July 16, 1969, at Cape Canaveral, Florida, picturing Commander Neil Armstrong (left), Command Module Pilot Mike Collins (center), and Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin (right). As the crew journeys to the Moon, Earth recedes to the size of a basketball, a baseball, and then it is the size of a bright blue marble.

Flying into the lunar shadow on July 19, 1969, the crew views the Moon as a startling yet magnificent sphere radiant in the glowing light blue light of earthshine. Craters on the Moon are seen in an eerie highlighted detail with a third of the Moon masked by a black crescent. The crew feels tension building for their upcoming lunar landing as they look down and view the landing area in the Moon's Sea of Tranquility.

Mike Collins pushes the button to release the lunar module Eagle from the command module Columbia and comments, "Ok, there you go! Beautiful!" as astronauts Armstong and Aldrin in LM Eagle spring away from the command module to begin their transit to the Moon's surface on July 20, 1969.

As they separate from Columbia, Neil Armstrong radios to Mike Collins, "The Eagle has wings!" Mike Collins in turn replies, "I think you've got a fine looking flying machine there, Eagle, despite the fact you're upside down." Armstrong and Aldrin laugh and then start on their short trip from Columbia to the lunar surface. The spacecraft has only 12 minutes worth of fuel for their powered descent. The airless environment of the Moon necessitates Eagle to be under power every foot of the way down to the lunar surface.

At 34,000 feet altitude from the lunar surface, Armstrong and Aldrin are startled by the buzzing of Eagle's main computer alarm signaling a computer overload condition. Armstrong immediately knows that if this program alarm continues, he will have to abort their landing. Houston's Mission Control quickly assumes some tasks, a quarter million miles away from the lunar descent in progress. CapCom Charlie Duke confirms the landing can proceed, and says, "We're ‘go' on that alarm," as long as the alarm is not continuous. The LM's onboard computer system continues to steer the spacecraft to its landing point at Site 2 in the Sea of Tranquility.

A thousand feet from the Moon's surface, Neil Armstrong sees a large crater several hundred feet across and looming directly ahead of them in the proposed landing area. An extensive boulder field also surrounds the crater with some boulders are as big as small cars. Armstrong quickly surmises, too many rocks. He flies Eagle over the boulder field to a clearer landing area ahead. With only thirty seconds of fuel remaining and twenty feet to go, Armstrong is flying "dead man's curve," a flight profile too low to abort the landing if they run out of fuel and also out of time. Dust flies everywhere in a miniature lunar dust storm, almost obscuring the lunar landing area. As the lunar module descends further, neither Armstrong nor Aldrin sense Eagle landing.

Buzz Aldrin monitors his instrument panel and then calls out, "Contact light. Ok, engine stop," as Eagle touches down on the surface. Neil Armstrong hits the engine stop button and replies, "Shutdown." It suddenly becomes very quiet, and then both astronauts look at one another and clasp their gloved hands together in joy and amazement. Armstrong, thinks for a few seconds, keys Eagle's mike, and succinctly reports, "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed."

Neil Armstrong reaches the bottom of Eagle's ladder but pauses to review the situation. The LM's legs were designed to compress with the force of landing on the Moon. In turn, this would bring the ladder for leaving the lunar module close to the lunar surface. However, Eagle had landed too gently for that to have occurred. Armstrong was a good three feet from the lunar surface on the last ladder rung.

He puts his leg out and then pushes off with a slow motion fall onto the lunar module's supporting footpad. Making sure he can get back onto the ladder if necessary, he springs upward and easily manages to regain the ladder. Neil Armstrong then descends the ladder one rung at a time to the lunar module's footpad.21 As he steps onto the lunar surface, Armstrong says, "That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind." It was 9:56 pm, Houston time; Apollo had walked on the Moon.

As Armstrong looks around, Eagle has landed on a broad level plain, marked here and there with Moon craters, some a few dozen feet apart to much smaller ones only inches apart. The area also is strewn with rocks and boulders. On the horizon, Armstrong sees ridges he thinks are twenty to thirty feet high, but without trees or buildings to judge dimensions, it is difficult to tell. Lack of a lunar atmosphere gives a dramatic clarity to his view. Things appear clearer than the clearest day on Earth.

Aldrin looks closely at the plains of the Sea of Tranquility where they have landed. The landscape curves gently but noticeably away from the landing area. The horizon is estimated at a mile and a half away, but Aldrin's vision is remarkably clear. Unlike viewing a landscape on Earth, Aldrin easily sees the Moon's horizon curvature. He is able to see that he and Armstrong are standing on a sphere.

"It has a stark beauty all its own," opines Buzz Aldrin, watching his crewmate Neil Armstrong walking on the Moon. As Aldrin comes down Eagle's ladder and steps onto the lunar surface, he exclaims, "Beautiful view!" Armstrong observes it is easier to move around on the lunar surface than he expected. Armstrong's space suit and his body weight are 348 pounds on Earth. On the Moon, both weigh only 58 pounds.

Both astronauts note that their walking on the Moon seems very familiar. The NASA training simulations they had gone through during their workup had been that good.24 Aldrin's space helmet faceplate reflects the image of Armstrong taking his picture. The reflection in Aldrin's helmet faceplate is one of only a few pictures of Neil Armstrong at the landing site.

Tranquility base now very much looks like an exploration site with artifacts of the crew's stay strewn here and there. An American flag in a frozen countenance is testimony to their picture taking session just a few hours earlier. A television camera on its tripod also bears testimony to their landing and will record their launch from the lunar surface back to CM Columbia orbiting overhead. A little bit further away, two scientific experiments stand like sentinels to the lunar landing.

The area near the lunar module is visibly marked with the astronauts' busy footprints and distinctive tread marks from their Moon boots. Their footprints will remain the same for a million or more years, with only random micrometeorites to wear them down over time.

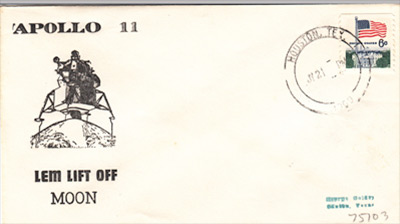

Collins tries to pinpoint where in the Sea of Tranquility, his fellow crew members are located but to no avail. The crew's success to rejoin Collins relies upon Eagle's single 3,500 pound thrust, hypergolic rocket engine. The engine had to work and work long enough to get back into orbit.28 Aldrin begins the Eagle's final countdown. At the five second mark, Armstrong relays "engine arm, ascent, and proceed" commands. Aldrin hits the "proceed" button, there's a pause, and Eagle's rocket engine fires. He yells, "We're off!"

In his astronaut sextant, Mike Collins sees the tiny LM rocketing up to Columbia so steadily it seems to be unreal. Wielding his camera and running back and forth to view the rendezvous out Columbia's windows, Collins captures the momentous sight in an iconic photo of the Moon, LM Eagle, and the Earth and says to his crewmates, "I got the Earth coming up behind you—it's fantastic!"

After the crew docks with Collins in Columbia, they pass up two virtually weightless boxes of Moon rocks and lunar soil samples zipped into two larger white cloth bags. Armstrong and Aldrin reenter Columbia through Eagle's access tunnel and close the hatch behind them. The lunar module is just dead weight now. With Eagle's mission completed, the faithful and dependable lunar module will be jettisoned into Moon orbit.

A little after midnight on July 22, 1969, and still in lunar orbit, Command Module Pilot Mike Collins restarts Columbia's Service Propulsion System rocket engine. Three minutes later, the spacecraft is rocketing on its trajectory back to Earth. The rocket engine burn is as perfect as the one placing Columbia in lunar orbit two days previously. Collins is ecstatic with the rocket burn and remarks, "Beautiful burn, SPS, I love you! You are a jewel." Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins in Columbia are on their way home!

The Apollo 11 crew rests, relaxes, and like tourists, take pictures on the trip home, but mostly "just waits" as Columbia speeds along its transearth injection track, watching the Earth become bigger and bigger. The crew enjoys televising life in their spacecraft to an estimated 600 million people on Earth who are viewing Apollo 11's flight and the crew's mission progress.

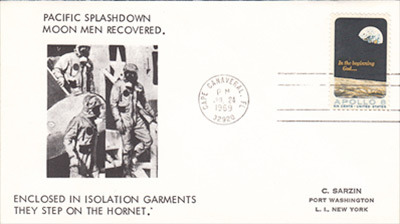

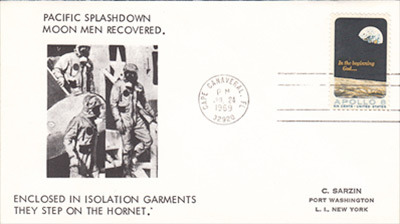

At 1:16 pm Houston time, Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins step out of the USS Hornet's recovery helo onto the carrier's aircraft elevator and the ship's hangar deck. They truly look like Moon-men in the quarantine gear provided to them by the UDT team assisting their recovery. NASA officials require a quarantine period of 21 days to assure the crew has not brought back "Moon germs" to Earth from their sojourn on the Moon.

In the UDT recovery life raft, the Apollo 11 astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins are scrubbed down with iodine solution by the UDT recovery swimmers and in turn, the astronauts scrub down the swimmers. The UDT team additionally has to scrub down the Command Module Columbia before it is brought aboard the primary recovery ship USS Hornet.

Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins in their quarantine gear debark from the recovery helo and walk across the hangar deck of USS Hornet and into the waiting Mobile Quarantine Facility where they will spend the next 21 days recounting their landing on the Moon, debriefing their flight, and waiting to be medically cleared from quarantine.

Several years later, USS Hornet Commanding Officer, Captain Carl Seiberlich, was asked by the author as to what he considered the most difficult part of the recovery of the Apollo 11 crew. His unhesitating comment was the strict precautions to assure that the Apollo 11 crew took necessary quarantine precautions and had not carried back "Moon germs."

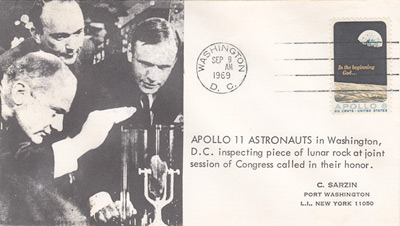

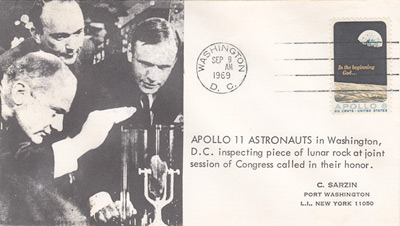

Buzz Aldrin, Mike Collins, and Neil Armstrong look closely at one of the Moon rocks brought back by them after landing on the Moon. In recognition of their heroic achievement, President Richard M. Nixon awards the Apollo 11 astronauts Presidential Medals of Freedom, August 13, 1969, in an awards ceremony.

The Apollo 11 crew has taken the goal made by President John F. Kennedy, back in 1961, to take on a goal for a manned mission to the Moon, He commented, "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal before this decade is out of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth." That goal now has been achieved, and the crew of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins, have completed their mission and are safely home!

— Steve Durst, SU 4379