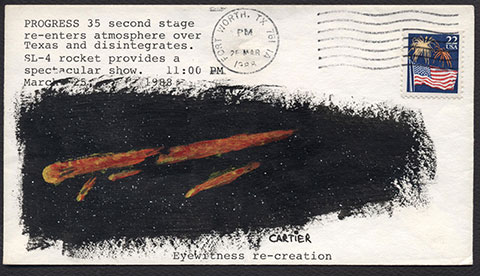

Space Cover #404: Soviet Nuclear Crashes in the AmericasAround 11:00 PM on Wednesday evening March 25, 1988, I was loading some items in my trunk as we left my brother's home for our home 45 miles distant. My daughter called out in a very concerned voice, "Dad. Dad. Wh-what's that?" as she pointed out to the sky a little above the horizon.

I peered around the door of the trunk and looked in the direction in which she was pointing. A large yellow and red ball with a long, but broken tail was slowly moving across the sky and drifting downward. Behind and below it were two smaller lit pieces that had broken off and were now falling lower in the sky. "Don't worry," I assured her. "It's a pretty big satellite burning up as it's entering the earth's atmosphere".

About then my eldest son and my wife came out of the house and I told them all, "Right now, take a very close look at the size, the number of pieces and the colors of what you're seeing at this moment. Really concentrate because I want to have Jon (our other son) draw this from our memories." As I said this another piece broke away and was flying on the same plane, but below the main piece of burning hardware.

During our drive home we listened to reports of a plane crashing at Carswell AFB, at Dallas-Ft. Worth Airport or at Love Field, dependent on where the viewers were located. One man even declared that it was a commercial 727 jet passenger plane and that he saw people in the windows. But by the time we got home NORAD had advised radio networks that it was the Soviet Progress 35 cargo resupply vehicle that had been released from the MIR space station with a load of trash and station discards. They described it as being as large as a school bus.

At home we all agreed on the pencil sketch I made and the colors that I had written in for each of the five pieces we had seen. I took 10 covers to the Ft. Worth Post Office where a March 26, 1988 machine cancel was applied. Later my son took a wet brush and painted a swab of black across the covers and then feathered it all around with a dry brush. When it dried he painted in the reds and yellows that we all agreed were an accurate visual description of what we had witnessed.

The reason that I had been so sure of my statement was that this was not the first re-entry I had been fortunate enough to witness. I had previously seen the demise of Sputnik 3 during its re-entry in the wee hours of April 6, 1960 while taking my brothers to watch a six Science Fiction movie marathon of films at a drive-in theater. That ball of flame was a brilliant white and about one quarter the size of the moon. Sputnik 3 had been launched on May 15, 1958 and was possibly the first satellite to disintegrate in view of humans. This incident helped lead to my hobby of Astrophilately and made me aware of the re-entries of satellites.

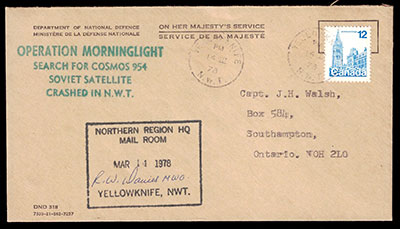

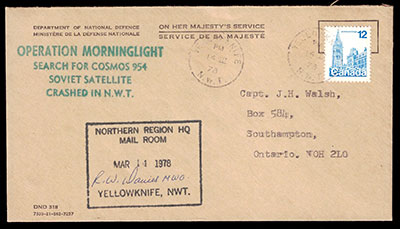

It was at a TEXPEX show back around 1992 that I found a strange cover in a dollar box. It bore a Canadian definitive stamp and the corner card showed that it was from the Department of National Defense. Under that was a rubber stamp in green ink that read:"OPERATION MORNINGLIGHT / Search for Cosmos 954 / Soviet Satellite / Crashed in N.W.T." (Northwest Territories). It had been mailed to a Captain in the Canadian Mounties in Southampton,Ontario from the Northern Region HQ Mail Room in Yellowknife, N.W.T.

I had never heard of a Soviet satellite crashing in North America and looked up Cosmos 954 on the internet. That led me to a book, "Operation Morning Light – Terror in our skies" by Leo Heaps. It is one of the most gripping science fact books that I've ever read.

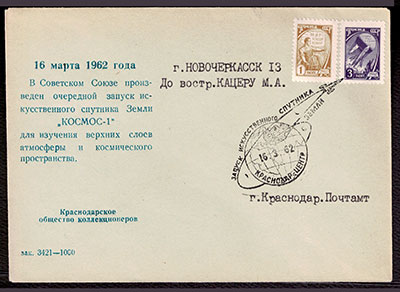

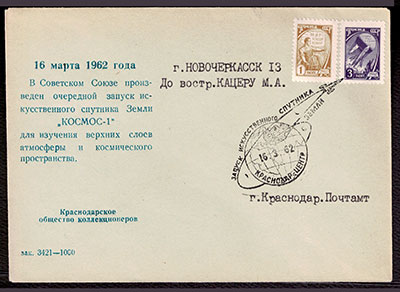

Cosmos 1 launched on March 15, 1962 was called a "Technology" satellite and was the first of what have to date become over 2,500 Cosmos satellites. Primarily for reconnaissance (spying) they were also used for Radar Tracking, Technology, Communications, Anti-satellite satellites, Early tests of the Vostok and Soyuz capsules, Weather, Venus probes Solar and Lunar probes and a host of other reasons. The covers are not popular among United States collectors as manned launch or landing covers.

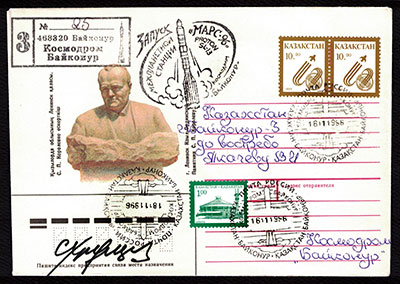

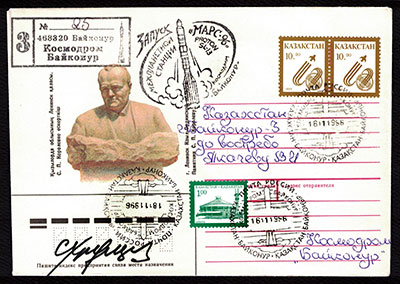

Cosmos 954, a spy satellite, estimated to be about fifty feet long and weighing around five tons, had on board 110 pounds of highly radioactive, dangerous Uranium 235, because in the 1970s solar panels were too inefficient to keep the satellites, especially those in low orbits, orbiting. Launched on September 18, 1977 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome Cosmos 954 encountered a series of malfunctions which led to the loss of control of the satellite.

On December 15, 1977 North American Air Defense (NORAD) in the United States' Rocky Mountains noticed the wavering of the craft and contacted the Soviet Union authorities who assured them that they had total control of the satellite and were just using various tests to move it about. They reported having a failsafe mechanism that would break the satellite into three pieces, jettisoning the nuclear pack into a 900 mile higher orbit where it could stay in space for 1,000 years.

But as the orbit continued decaying, NASA scientists predicted that the craft would burn up in the atmosphere by April, 1978. A U.S. group known as the Nuclear Emergency Search Team (NEST), operating out of Las Vegas, Nevada joined in watching the errant craft. It is a group ready to counter any radiation hazard in the world. They had been highly involved in the B-52 crash in January of 1965 which caught fire and crashed on the sea ice near Thule, Greenland. On board were four plutonian bombs which NEST had to safely recover along with tons of contaminated snow and ice.

There was special concern about Cosmos 954 as it made many passes directly over the North American continent. And new data showed that the nuclear powered satellite might reenter the atmosphere in late March. There was a concern that the heat of re-entry could result in a Hiroshima sized explosion over a populated area. Other national leaders were now brought up to date on the situation and the Soviets dropped all pretenses of having control of the satellite but only told the Americans that Cosmos 954 was not an atomic bomb.

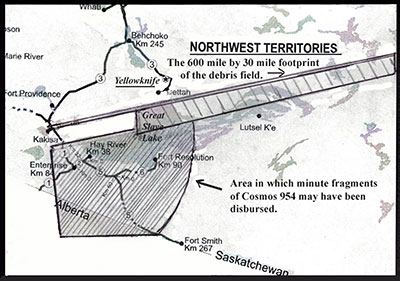

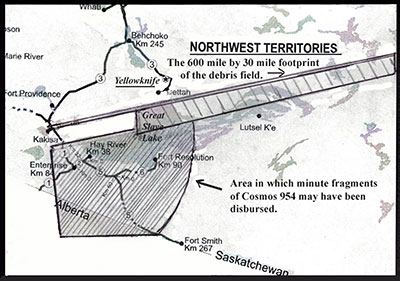

Fast forward and the satellite disintegrated over the western edge of the Northwest Territories of Canada, and there was no atomic explosion. But hundreds of radiated pieces of the huge satellite fell across a 370 mile by 30 mile wide swath of the N.W.T. scattering radioactive debris far and wide shortly after flying directly over Miami and then Detroit and then Las Vegas. The contamination levels were high.

The story of the search in -70 degree weather is a salute to the Canadian and Americans who worked to try to keep people away from debris as they collected and shipped it off. Had the accident occurred over a major city, it is likely that tens or even hundreds of thousands of people would have been afflicted with severe radiation poisoning.

The Soviets paid the Canadian government only $3 million of the requested $6 million cost of the cleanup which went under the code name, Operation Morning Light. However less than 1% of the debris was ever found and properly disposed of.

The Canadian Operation Morning Light cover shown above was cancelled on March 18, 1978. On that date an Inuit riding in a dog team pulled sleigh noted, and reported, a huge uplift of ice in the middle of a lake. Searches in the ultra-freezing weather were unable to locate whatever it was that crashed into that ice covered lake.

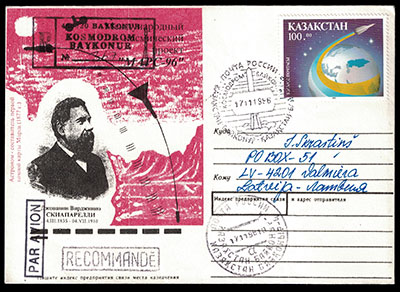

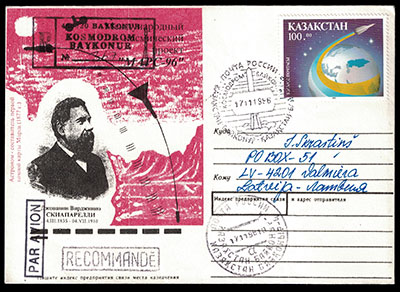

Cosmos 954 was not the only nuclear powered spacecraft to have crashed in the Americas. Launched on a Proton rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, which now exists in Kazakhstan, the Soviet craft, Mars 1996, lifted off successfully on November 16, 1996. This actually started as, Mars-92 and was scrubbed. Then it was to have been the Mars-94 project. Originally, Mars-94 was to include a pair of spacecraft. One of them was to carry a Mars rover and another, a Mars orbiter. As the project slipped to 1994, due to financial problems, only the orbiter survived the cut. The orbiter had to be delayed to 1996, prompting a delay of the rover to 1998 and later leading to its cancellation.

After a 10-month journey, Mars-96 would enter the orbit of Mars on Sept. 12, 1997, to start at least a year-long mission. At the time, Mars-96 was expected to be the largest research vehicle designed to travel across the Solar System. In fact, the Block D upper stage would not have enough power to send the spacecraft from its initial parking orbit on its escape trajectory toward Mars after launch from Baikonur .The upper stage would accelerate the spacecraft by 10,335 feet per second and the probe would then use its Autonomous Propulsion Unit to add another 1886 feet per second.

The Proton rocket's three booster stages and the first burn of the upper stage went as scheduled, delivering the spacecraft to an initial Earth orbit at an altitude of around 100 miles. The second firing was scheduled to take place one hour, eight minutes after liftoff and beyond the range of Russian ground control stations. The maneuver would deliver 10,335 feet per second in acceleration, followed by the firing of the ADU propulsion unit onboard Mars-96 to escape the Earth orbit and start a path toward Mars. However, it misfired, apparently delivering 65 feet per second in the wrong direction.

The spacecraft then separated from the upper stage at the beginning of the 2nd orbit. Its solar panels and other external elements had deployed and the ADU propulsion unit fired, in an effort to make up the necessary speed, which was now impossible. Instead, due to the wrong orientation, the maneuver actually pushed the spacecraft to as low as 47 miles, causing the spacecraft to lose its orbital velocity and sending it toward reentry. Communications were never restored between the controllers at Baikonur and the satellite.

At that time, according to both the Soviet Union and to the American NORAD, the Mars-96 spacecraft burned up over the Southern hemisphere with surviving debris reaching the ocean surface somewhere between Easter Island and the coast of Chile. However, several days after the report of the loss, I saw a three column inch story in the Ft. Worth Star-Telegram newspaper stating that American and Chilean military were conducting a joint exercise in the interior of Chile.

From what I had read about the false information surrounding the earlier Cosmos 954 satellite, I began to believe that the Mars '96 payload actually crashed on land in Chile. A week or so later, reports from small towns and villages about a fireball falling near the Bolivia-Chile border in the Andes caused NORAD and the USSR to admit that the space probe had actually crashed on land. Had those reports from civilians never made the local press, the actual story of Mars '96 would have ended with the cover up. News about the search and the radiation debris has not surfaced yet to the best of my knowledge.