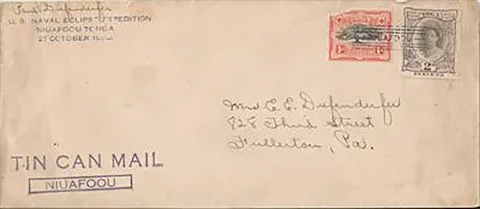

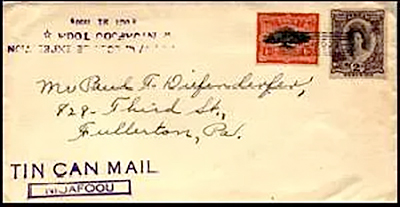

Space Cover #210: Rocket and Tin Can Mail at Niuafo'ouThe pictured cover is from the U.S. Naval Eclipse Expedition at Niuafo’ou Tonga on October 21, 1930 and was sent by Paul Diefenderfer (signed above the eclipse wording) who was the chief photographer for this expedition. In researching this cover I found the following write-up of rocket and tin can mail from Niuafo’ou authored by Betty Billingham. The full write-up can be found here with more Tin Can Mail images and additional description of later Tin Can Mail and why it ended in 1983.

This story begins back in 1882 when William Travers, a plantation manager, found himself 'marooned' on this tiny doughnut-shaped island of Niuafo'ou located half way between Fiji and Samoa. It is nothing more than the tip of a volcano jutting out of the vast blue waters of the Pacific. Just a couple of miles out, he could see the passenger liners steaming past, but none ever called because the island had no harbour and no beaches. In fact the steep sides plunge six miles down to the bottom of the Tongan Trench making it impossible to anchor and hard to land even a rowing boat.

The only white man on the island, Travers resented being unable to communicate with the outside world. So when the need to contact his company in Australia became desperate, he came up with an ingenious plan.

He wrote to the Tongan postal authorities asking them to seal his mail in a ship's biscuit tin, and arrange for the captain of one of the Union Steamship Company vessels to throw it overboard as they passed the island on their way between Suva and Fiji. These ships traded regularly between the islands of the Pacific. If the captain would give a hoot on the ship's siren, he would send a swimmer out to collect the tin.

Carefully he wrapped this letter in grease-proof paper and tied it to a short stick. He approached the strongest swimmer on the island and asked him to swim out to the next ship and hand his letter to the captain. In this way Tin Can Mail was born. It was to become a regular happening after Aurthur Tindall set up as a trader on the island some years later.

The island's fisherman were well used to swimming in the dangerous shark-infested waters, which they did clinging to a long buoyant fau pole cut from a type of hibiscus. By putting a pole under one arm they could float and fish for hours on end.

However, the strong currents meant that a swimmer might often struggle for up to six hours to retrieve a mail tin dropped from a ship only a mile off shore. In stormy weather it proved impossible to collect the mail and any number of other methods were tried. In 1902 William Edgar Geil wrote in his book 'Ocean and Isle' that he had watched the captain send letters to the island by rocket. On this occasion the attempt was successful, but often the rocket overshot the island altogether, landed in the lake in the centre, or just got lost in the undergrowth. On a previous occasion the package of letters had burst into flames en route. The arrival of the rocket was an event that caused the entire population to down tools and watch. Then began the mad scramble to retrieve the package and collect the reward.

Charles Ramsay, who had been hospitalised for several years after being severely gassed in the First World War, came to Niuafo'ou as a plantation manager in 1921. He too needed to communicate with the outside world and took over the task of swimming the mail. The only white man to do so, he went out 112 times in all weathers. If a ship happened to pass at night it would blow its siren and the swimmers would go out as a group, one carrying a lamp. Back on shore they would build bonfires to guide the swimmers home to the tiny island.

The next phase in the Tin Can Mail saga came when Walter George Quensell arrived on the island in 1928. He quickly realised that philatelic interest could be generated by this unique method of delivering the mail and so, with a child's printing set, he produced a rubber stamp which read "TIN CAN MAIL" and applied it to all outgoing letters.

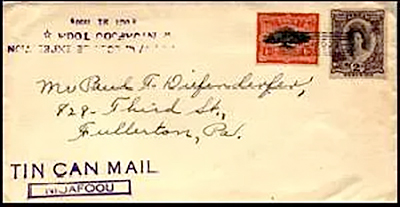

The total eclipse of the sun in 1930 was best viewed from Niuafo'ou and had a major impact on what was now known as Tin Can Island. Paul Diefenderfer, the Director of Education in Suva, accompanied the American expedition as chief photographer. He liked the idea of cachets and the scientists were quick to produce one of their own to commemorate the occasion. Diefenderfer also persuaded Quensell to develop his idea further and have rubber stamps made in New Zealand.

Inevitably one of the 'postmen' was attacked by a shark and died. On his deathbed he confessed that, in a temper, he had opened the tap on one of the huge concrete fresh water tanks. This was a great crime because the island had no fresh water and rain water had to be collected during the hurricane season and stored. The Chief pointed out that what he had done threatened the very existence of the inhabitants and said that the Gods had justly punished him.

As it happened there were no further incidents in which sharks were involved - and no further tampering with the water supply!

Pictured above is a second cachet from the eclipse expedition.

I have been unable to find any reference to any of the actual rocket mail from Niuafo’ou in any exhibits or collections. Though it is doubtful any markings would have been on the mail marking it as rocket mail what a find it would be.