Space Cover #157: NASA Comes, Cities GoLogtown Mississippi was established in the early 1800s. This old town was located just south of what is now NASA's Stennis Space Center east of the Pearl River and south of Picayune.

This once booming town actually got its name from the logging industry and supplied logs to New Orleans. The unnamed location was known as "The Log Town," and the name stuck. The town operated along the Pearl River as part of large chain of lumber mill industries, which boomed after the Civil War and became one of the largest lumber industries in the world. With the coming of the Great Depression, many of the mills closed, except one that was located on the Pearl River at Gainesville. The town was alive until it was sold by the state to NASA in 1961. In the end, Logtown and five of its neighboring towns were bulldozed into the ground, sparing only the cemeteries and roads.

Logtown was one of several towns once located within the acoustic buffer zone of the Stennis Space Center. The town's economy relied largely on logging and shipping, with the first mill supposedly built in 1845 by E. G. Goddard of Michigan. In 1889, Henry Weston founded the H. Weston Lumber Company, a massive undertaking which transformed Logtown into one of the largest lumbering centers in the United States. This mill employed 1,200 men, and had over 20 barges and 4 two-masted schooners. At its peak, Logtown had approximately 3,000 residents, most associated with the lumber business.

The company operated in Logtown until 1930, by which time the supply of merchantable timber had been exhausted. The town rapidly declined in population and industrial importance. By 1961, when the area was being considered by NASA for the development of an engine test facility, there were only 250 residents.

Other towns once located in what is now the SSC facility include Gainesville, once the county seat, Napoleon, The Point, Santa Rosa, Westonia, and Dillville.

Similar to Logtown, Gainesville, which once was the county seat and economic center for the entire area, had only one store left to serve its 35 families and 100 residents. The hotels, stores, taverns, and most of the homes of Gainesville had vanished.

Roy Baxter, Jr., was among those in the Logtown area at the time NASA arrived in 1961. Baxter often flew fishermen out to the barrier islands in a Cessna 180 seaplane that he co-owned with a friend. On 25 October, he had been to New Orleans to gas up his plane for a fishing trip the next day. While flying home, he looked at his watch and noticed it was time for the five o'clock news from the radio station WWL in New Orleans. Missing some of the report, Baxter heard enough to be alarmed and puzzled as he learned that the federal government was going to acquire vast amounts of land by eminent domain along the Pearl River and build a facility to test rockets bound for the Moon. When he landed and taxied the plane up to its dock, his mother Gladys met him on the banks of the river and said, "We've got some bad news."

At first, many people in the Logtown area did not comprehend the full extent of the federal government's plan. Baxter himself looked up the term "eminent domain" in the dictionary to be sure of its meaning. According to Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, the term means "the right of the government to take (usually by purchase) private property for public use." Once the town realized the magnitude of the announcement, chaos ensued.

Just up the river, at Gainesville, Alton D. Kellar and his neighbors were "shocked," and some never reconciled to the news. The day of the announcement, Kellar's father told Alton that "Moving is for you folk, it's not for me." Kellar responded, "Dad, you know we've all got to move when the government condemns a place like this." His father replied, "Well, you go on." A year later, the senior Kellar died of a heart attack, even as the movers had come to jack up his house.

Other longtime residents received the news with mixed emotions. On the one hand, they felt confused and saddened about the prospects of being displaced. On the other hand, they looked to the future and pictured the NASA operation as a positive, economic force for the Gulf Coast. Leo Seal, Jr., president and chairman of the board of Hancock Bank, was one of these individuals. Seal, born and raised in Bay St. Louis, spent most of his adult life in Hancock County and recalled that people in the county received the news in "disbelief." Seal found it difficult to comprehend in 1961 that NASA proposed to spend such an enormous amount of money on the Mississippi project. An ardent supporter of the NASA project from the very beginning, Seal welcomed the test facility with "open arms."

The (New Orleans) Times-Picayune carried a big headline that read "660 La.-Miss. Families Must Leave Testing Site." Without delay, the federal government began the legal action necessary to acquire land for a Moon rocket testing site. The families that had to be relocated lived in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, and Hancock and Pearl River Counties in Mississippi. Therefore, condemnation suits were filed in U.S. Courts in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Jackson, Mississippi, and a timetable of 2-1/2 years was established to complete the removal process.

Governor Ross Barnett (D-Mississippi) said he was "happy" to know that NASA had decided to locate in south Mississippi. He pledged "full support" of the project and predicted great economic gains as a result of the project. Senator Stennis, at the time a member of the Armed Services Committee and the Aeronautical and Space Sciences Committee, told The Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger that NASA's decision "puts Mississippi in the space program and gives the state an unusually high military value in the program." He also said, however, that he regretted that families would have to be moved from the area. This aspect of the project concerned the senator for the rest of his career and played a major role in all of his dealings with NASA.

Soon after the effects of dismay and excitement were being felt by residents along the Pearl River and by the state's politicians, news media representatives from Jackson, Mississippi, New Orleans, Louisiana, and the local area descended on south Mississippi to obtain firsthand reactions. Emotions churned. Some people were ready "to take up arms" to defend their land. Roy Baxter of Logtown drove to Bay St. Louis to confer with Leo Seal, Sr., an influential community leader and personal friend of Senator Stennis. They decided to ask the senator to meet with the people. Seal telephoned Stennis and the senator agreed to a meeting at Logtown on All Saints Day, 1 November 1961.

If anyone had the ability to allay the people's fears and explain the need for the huge new project, it was John Stennis, the junior senator from Mississippi.

It was at the Logtown School Athletic Field that Senator John C. Stennis addressed some 1,500 people of the area to explain the plans to develop the new NASA facility. The senator was instrumental through this transitional period in securing funding for the relocation of families and the development of the center, of which he was a staunch supporter from the beginning.

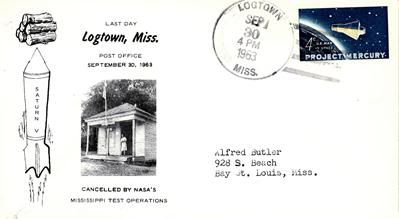

The cover above was for the last day of the Logtown Mississippi post office - postmarked at 4 PM on September 30, 1963. The cover states it was "cancelled by NASA's Mississippi Test Operations." Though I have seen this cover several times I have never seen such covers produced for any of the other cities "sold to the state" for the NASA Stennis Space Center.

Much of this post is taken from NASA publication SP-4310 Way Station to Space originally used to research this cover. So if you find one...