Space Cover 119: When the Race for Space Began The Soviet Union had captured the imagination of the world by sending men higher than anyone had ever gone before. America's response was made shortly afterward by a naval officer and a Marine officer. Their names were not Shepard and Glenn, and the time was not the Sixties, but the Thirties. In an all-but-forgotten flight, two American military men carried their country's colors to a world altitude record and began the race for space...From the article; "When the Race for Space Began" by J. Gordan Vaeth printed in Proceedings August, 1963

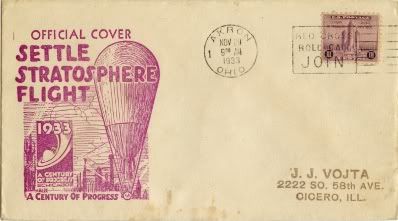

The history of the United States' manned space program is usually thought to begin with the Project Mercury. But it can be argued that it actually began in the early part of the 20th century and consisted solely of manned balloon flights into the stratosphere. On one such flight Major Chester L. Fordney (USMC) and Lieutenant Commander T.G.W. ("Tex") Settle (USN) launched their balloon into the stratosphere from the Goodyear-Zeppelin facilities in Akron, Ohio, watched by only a few hundred spectators on November 20, 1933 around 9 a.m. The round metal gondola was seven feet in diameter and was attached to a 600,000 cubic foot hydrogen filled balloon. Several scientific instruments were flown for measuring cosmic rays and a radio to communicate with the ground. The flight received national publicity as the first live radio transmissions from the stratosphere were broadcast on radio networks.

The spherical gondola had a deck, four feet in diameter, to stand upon. Three tiers of shelves circled its interior. Deck and shelves were supported by eight vertical stanchions attached directly to the load ring atop the gondola. Ten observation ports, three inches in diameter, had been built into the shell along with two hatches, each with an airtight double door. To control internal temperature, the upper half of the outer surface from the gondola's equator to 60 degrees North latitude had been painted white, the lower half, black.

Their ascent did much more than begin the race for space. It pioneered the sealed cabins and life support systems used in manned spacecraft today. As far as is known, it was the first flight to expose living organisms, spores, directly to conditions at the top of the atmosphere. It is believed to have been the first flight in which the biological effects of very high altitude radiation upon human beings was the subject of serious concern and study.

Settle and Fordney rode no rocket. They could hardly be called astronauts in today's sense of the word. They were, however, the first Americans to reach, enter, and remain for any period of time (two hours) in a space equivalent environment. In this sense, they were America's first men-in-space-and the press and public of the times considered them such.

Float altitude was reached around 2 p.m. The flight reached a world altitude record of 61,237 feet (note: this was 1083 feet shy of the then unofficial altitude record set in the Soviet Union by the USSR-1 high-altitude balloon in October 1933 but the altitude was not recognized by the FAI - Federation Aeronautique Internationale). The balloon reached a speed of 55 miles per hour as the balloonists were carried eastward towards the Atlantic Ocean coast. At one point the balloon began to quickly lose altitude and Commander Settle informed Major Fordney that he might have to parachute overboard as ballast - fortunately this was not necessary and Major Fordney remained in the gondola.

The balloon landed at 5:50 p.m. in a swamp just outside Bridgeton, New Jersey. Because it was not certain just where the balloon would land, a coast guard plane and cutters were ordered to prepare for a search in the ocean. Meanwhile, every town in southwestern New Jersey had been contacted by telephone by the State Police. State Troopers, residents and newspapermen "searched the roads and penetrated the woods" for the balloonists, who had dumped their radio batteries during the descent. They were finally recovered, safe and sound, the following day and were pulled out of the swamp in a kayak.

In January a response from Maxim Litvinoff, Foreign Commissar of the Soviet Union, came this message:

Hearty congratulations on your great achievement. I am sure that your colleagues in the Soviet Union have watched with greatest interest your flight. May both our countries continue to contest the heights in every sphere of science and technique.

"Continue to contest the heights" they would do... So if you find some early stratospheric covers...